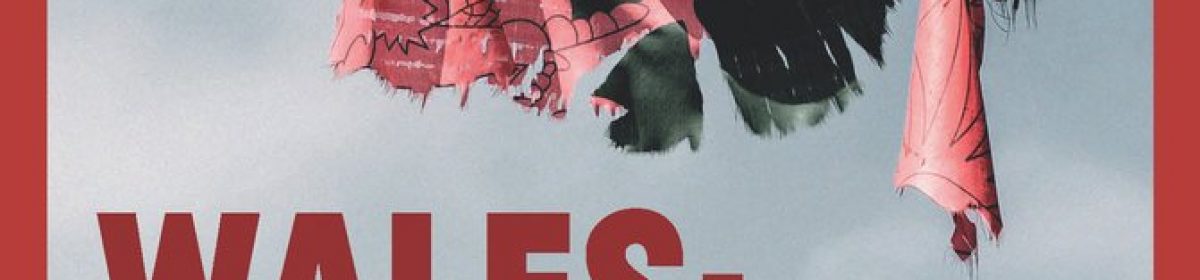

Image credit: The Welsh Football Collection, Wrexham County Borough Museum & Archives.

This cotton Wales football shirt was worn by Nick Deacy of PSV Eindhoven in an under 21s international match against Scotland in 1977. The two nations had been competing against each other since 1876, making it the second oldest international fixture in world football. The shirt is part of the collections of the new national Football Museum for Wales in Wrexham, the town where the Football Association of Wales (FAW) was created. The museum documents Wales’ position as one of the formative nations in world football.

This shirt design was worn by Wales from 1976 to 1979 and has become iconic in Welsh football culture. Fan culture is often deeply nostalgic, especially amongst older men lamenting the passing of their youth. Much of this nostalgia centres on the 1970s and 1980s terrace culture that lost its focal point with the introduction of all-seater stadiums in the 1990s. Terrace culture was occasionally violent but always boisterous and often deeply concerned with style and aesthetics. During the 1970s and 80s, fashionable football fans rarely wore replica shirts but now those same fans are older they have become interested in the kits of yesteryear. To meet this demand, the FAW released a new version of this kit during the 2016 European championships. It sold well and continues to be worn at Wales matches. Many who bought the 2016 reissue were far too young to have seen Wales play in the original version but by wearing it they were showing themselves to be supporters who knew Welsh football history; it perhaps helped mark them out as authentic fans. Yet the reissue itself was not authentic. Copyright and commercial issues meant that it did not feature the logo of the original manufacturer Admiral.

The Admiral trademark had been in use on clothing since 1914 and in 1973 it appeared on Leeds United shirts. This was the first time a football shirt in the English first division had been branded. The Leeds shirt design was copyrighted and put on sale to fans, making the company a pioneer in manufacturing replica kits for supporters. Admiral also helped drive forward more colourful and creative football shirt designs, as it sought to take advantage of the new visual possibilities that football on colour television presented.

One such design was the tramline design featured on this Wales shirt, a design which had already been used by Admiral in kits for Coventry City and Dundee. The FAW described the colouring of their version as ‘Red with Yellow and Green trim’. Welsh national sporting outfits are red because of the dragon that forms the basis of the Welsh flag and which gave the FAW the symbol on their badge in the shirt’s centre. The green in the stripe and badge also came from the Welsh flag. Yellow had been used for change strips by the Welsh national side since 1949 and is the colour of the daffodil, the national flower of Wales. It also featured prominently on the coat of arms of the House of Aberffraw, a Welsh medieval dynasty that resisted English intrusion into Wales.

The last part of Wales under native rule fell to English control in 1283 and the Welsh nation was formally annexed by England in the sixteenth century. Although the majority of Welsh people accepted English rule, a strong sense of Welsh identity remained, not least because of the prevalence of the Welsh language. It was still spoken by probably eighty percent of people in the early nineteenth century, when Wales was undergoing economic and cultural transformation thanks to its rich deposits in coal and iron ore. While the Welsh language had begun to decline significantly, there was a renaissance in Welsh national pride in the late nineteenth century. Thus, when England and Scotland formed national associations and began playing each other, first in football and then in rugby, Wales quickly followed suit. It was Wales’ cultural assimilation into Britain that meant that organized modern sport was an important part of Welsh popular culture but it was Wales’ enduring sense of difference that meant this was utilized to celebrate and sustain Welsh nationhood.

Indeed, sport became one of the most important facets in Welsh identity in the early and mid-twentieth centuries. There was large-scale migration into industrial Wales at the start of the century and sport helped people form a connection with their new nation. The interwar depression saw that movement of people go into reverse and it inflicted on Wales an economic trauma that it has never fully recovered from. Migration also pushed the Welsh language further into decline and by 1961 it was spoken by just a quarter of the population. Some people were choosing not to raise their children in Welsh but others, who did not speak the language, resented any implication that this made them less Welsh. Some felt greater political autonomy was the answer to Wales’ problems. A language movement waged a campaign of direct action to win legal rights for the use of Welsh but a 1979 referendum on the creation of some form of Welsh parliament was lost amidst fears about the potential impact on the nation’s cultural, constitutional and economic future. Another referendum on the same question was won narrowly in 1997 and the demands for further Welsh political autonomy continue to grow, though not to universal acclaim.

Amidst such turmoil, and the divisions in Welsh society that it exposed and perpetuated, sport was something of a healer. It allowed people to celebrate their sense of Welshness but made no demands on people as to what Wales should mean. Welsh national teams could be supported by all regardless of their cultural and political backgrounds and beliefs. Indeed, few other cultural forms as sport were so well equipped to express national identity. Sport’s emblems, emotions, songs and contests all made it a perfect vehicle through which collective ideas of nationhood could be expressed. Sport has thus been a central tenet in inventing, maintaining and projecting the idea of a Welsh national identity in and outside its blurred borders. It has helped gloss over the different meanings that the people of Wales attach to their nationality, enabling them to assert their Welshness in the face of internal division and the political, social and cultural shadow of England.

Of course, results did not always match aspirations and the Welsh national football side has not matched its rugby equivalent for sporting impact and recognition. Wales has only twice played at the World Cup, partly because before 1939 the FAW shared the wider British disdain for FIFA and global football. Wales did reach the semi-final of the 2016 European Championships, and wearing this shirt, the 1976 quarterfinal of the same tournament too. At the beginning of the latter match, both the Welsh and British anthems were played. That was one of the last times the FAW played God Save the Queen, as football increasingly became a symbol of a single Welsh identity rather than a dual British and Welsh one. Indeed, at the 2016 European Championship, a fans’ banner proudly declared ‘Welsh not British’. That was not how the majority of Welsh people felt. But national identities are never static and Britishness does seem to be in decline in the 21st century raising questions about whether the United Kingdom can survive. Football has played a major role in sustaining Welsh identity and it will almost certainly have a role in contributing to its future direction too.

This essay was first published in: Daphné Bolz & Michael Krüger (eds), A History of Sport in Europe in 100 Objects (2023).

Further reading and references

“Admiral: Our History,” accessed 22 February 2022, https://admiralsportswear.com/history/

Johnes, Martin, A History of Sport in Wales (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2005)

Johnes, Martin, Wales: England’s Colony? The Conquest, Assimilation and Re-creation of Wales (Cardigan: Parthian, 2019).

Stead, Phil, Red Dragons: The Story of Welsh Football (Talybont: Y Lolfa, 2012).