A short video I made for a Welsh Government event about history in the Curriculum for Wales.

Category: education

The Curriculum for Wales, Welsh History and Citizenship, and the Threat of Embedding Inequality

Welsh education is heading towards its biggest shake up for two generations. The new Curriculum for Wales is intended to place responsibility for what pupils are taught with their teachers. It does not specify any required content but instead sets out ‘the essence of learning’ that should underpin the topics taught and learning activities employed. At secondary school, many traditional subjects will be merged into new broad areas of learning. The curriculum is intended to produce ‘ambitious and capable learners’ who are ‘enterprising and creative’, ‘ethical and informed citizens’, and ‘healthy and confident’.

Given how radical this change potentially is, there has been very little public debate about it. This is partly rooted in how abstract and difficult to understand the curriculum documentation is. It is dominated by technical language and abstract ideas and there is very little concrete to debate. There also seems to be a belief that in science and maths very little will change because of how those subjects are based on unavoidable core knowledges. Instead, most of the public discussion that has occurred has centred on the position of Welsh history.

The focus on history is rooted in how obsessed much of the Welsh public sphere (including myself) is by questions of identity. History is central to why Wales is a nation and thus has long been promoted by those seeking is develop a Welsh sense of nationhood. Concerns that children are not taught enough Welsh history are longstanding and date back to at least the 1880s. The debates around the teaching of Welsh history are also inherently political. Those who believe in independence often feel their political cause is hamstrung by people being unaware of their own history.

The new curriculum is consciously intended to be ‘Welsh’ in outlook and it requires the Welsh context to be central to whatever subject matter is delivered. This matters most in the Humanities where the Welsh context is intended to be delivered through activities and topics that join together the local, national and global. The intention is that this will instil in them ‘passion and pride in themselves, their communities and their country’. This quote comes from a guidance document for schools and might alarm those who fear a government attempt at Welsh nation building. Other documents are less celebratory but still clearly Welsh in outlook. Thus the goal stated in the main documentation is that learners should ‘develop a strong sense of their own identity and well-being’, ‘an understanding of others’ identities and make connections with people, places and histories elsewhere in Wales and across the world.’

A nearby slate quarry could thus be used to teach about local Welsh-speaking culture, the Welsh and British industrial revolution, and the connections between the profits of the slave trade and the historical local economy. This could bring in not just history, but literature, art, geography and economics too. There is real potential for exciting programmes of study that break down subject boundaries and engage pupils with where they live and make them think and understand their community’s connections with Wales and the wider world.

This is all sensible but there remains a vagueness around the underlying concepts. The Humanities section of the curriculum speaks of the need for ‘consistent exposure to the story of learners’ locality and the story of Wales’. Schools are asked to ‘Explore Welsh businesses, cultures, history, geography, politics, religions and societies’. But this leaves considerable freedom over the balance of focus and what exactly ‘consistent exposure’ means in practice. If schools want to minimize the Welsh angle in favour of the British or the global, they will be able to do so as long as the Welsh context is there. It is not difficult to imagine some schools treating ‘the story of Wales’ as a secondary concern because that is what already sometimes happens.

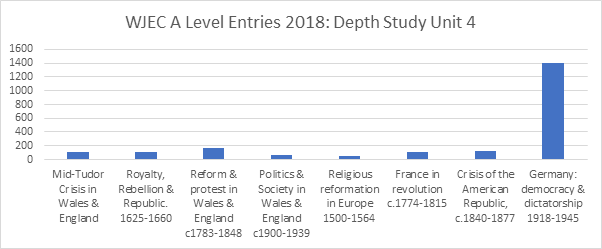

The existing national curriculum requires local and Welsh history to be ‘a focus of the study’ but, like its forthcoming replacement, it never defines very closely what that means in terms of actual practice. In some schools, it seems that the Welsh perspective is reduced to a tick box exercise where Welsh examples are occasionally employed but never made the heart of the history programme. I say ‘seems’ because there is no data on the proportion of existing pre-GCSE history teaching that is devoted to Welsh history. But all the anecdotal evidence points to Wales often not being at the heart of what history is taught, at least in secondary schools. At key stage 3 (ages 11 to 14) in particular, the Welsh element can feel rather nominal as many children learn about the Battle of Hastings, Henry VIII and the Nazis. GCSEs were reformed in 2017 to ensure Welsh history is not marginalised but at A Level the options schools choose reveal a stark preference in some units away from not just Wales but Britain too.

Why schools chose not to teach more Welsh history is a complex issue. Within a curriculum that is very flexible, teachers deliver what they are confident in, what they have resources for, what interests them and what they think pupils will be interested in. Not all history teachers have been taught Welsh history at school or university and they thus perhaps prefer to lean towards those topics they are familiar with. Resources are probably an issue too. While there are plenty of Welsh history resources out there, they can be scattered around and locating them is not always easy. Some of the best date back to the 1980 and 90s and are not online. There is also amongst both pupils and teachers the not-unreasonable idea that Welsh history is simply not as interesting as themes such as Nazi Germany. This matters because, after key stage 3, different subjects are competing for pupils and thus resources.

The new curriculum does nothing to address any of these issues and it is probable that it will not do much to enhance the volume of Welsh history taught beyond the local level. It replicates the existing curriculum’s flexibility with some loose requirement for a Welsh focus. Within that flexibility, teachers will continue to be guided by their existing knowledge, what resources they already have, what topics and techniques they already know work, and how much time and confidence they have to make changes. Some schools will update what they do but in many there is a very real possibility that not much will change at all, as teachers simply mould the tried and tested existing curricular into the new model. No change is always the easiest policy outcome to follow. Those schools that already teach a lot of Welsh history will continue to do so. Many of those that do not will also probably carry on in that vein.

Of course, a system designed to allow different curricula is also designed to produce different outcomes. The whole point of the reform is for schools to be different to one another but there may be unintended consequences to this. Particularly in areas where schools are essentially in competition with each other for pupils, some might choose to develop a strong sense of Welshness across all subject areas because they feel it will appeal to local parents and local authority funders. Others might go the opposite way for the same reasons, especially in border areas where attracting staff from England is important. Welsh-medium schools are probably more likely to be in the former group and English-medium schools in the latter.

Moreover, the concerns around variability do not just extend to issues of Welsh identity and history. By telling schools they can teach what they feel matters, the Welsh Government is telling them they do not have to teach, say, the histories of racism or the Holocaust. It is unlikely that any school history department would choose not to teach what Hitler inflicted upon the world but they will be perfectly at liberty to do so; indeed, by enshrining their right to do this, the Welsh Government is saying it would be happy for any school to follow such a line. Quite how that fits with the government’s endorsement of Holocaust Memorial Day and Mark Drakeford’s reminder of the importance of remembering such genocides is unclear.

There are other policy disconnects. The right to vote in Senedd elections has been granted to sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds. Yet the government has decided against requiring them to be taught anything specific about that institution, its history and how Welsh democracy works. Instead, faith is placed in a vague requirement for pupils to be made into informed and ethical citizens. By age 16, the ‘guidance’ says learners should be able to ‘compare and evaluate local, national and global governance systems, including the systems of government and democracy in Wales, considering their impact on societies in the past and present, and the rights and responsibilities of citizens in Wales.’ Making Wales an ‘including’ rather than the main focus of this ‘progression step’ seems to me to downplay its importance. Moreover, what this sentence actually means in terms of class time and knowledge is up to schools and teachers. Some pupils will be taught lots about devolved politics, others little. The government is giving young people the responsibility of voting but avoiding its own responsibility to ensure they are taught in any depth what that means in a Welsh context.

The new curriculum will thus not educate everyone in the same elements of political citizenship or history because it is explicitly designed to not do so. Just as they do now, pupils will continue to leave schools with very different understandings of what Wales is, what the Senedd does and how both fit into British, European and global contexts. Perhaps that does not matter if we want pupils to make up their own minds about how they should be governed. But, at the very least, if we are going to give young people the vote, surely it is not too much to want them to be told where it came from, what it means, and what it can do.

But this is not the biggest missed opportunity of the curriculum. Wales already has an educational system that produces very different outcomes for those who go through it. In 2019, 28.4% of pupils eligible for free school meals achieved five A*-C grade GCSEs, compared with 60.5% of those not eligible. In 2018, 75.3% of pupils in Ceredigion hit this level, whereas in Blaenau Gwent only 56.7% did. These are staggering differences that have nothing to do with the curriculum and everything to do with how poverty impacts on pupils’ lives. There is nothing in the new curriculum that looks to eradicate such differences.

Teachers in areas with the highest levels of deprivation face a daily struggle to deal with its consequences. This will also impact on what the new curriculum can achieve in their schools. It will be easier to develop innovative programmes that take advantage of what the new curriculum can enable in schools where teachers are not dealing with the extra demands of pupils who have missed breakfast or who have difficult home lives. Fieldtrips are easiest in schools where parents can afford them. Home learning is most effective in homes with books, computers and internet access. The very real danger of the new curriculum is not what it will or will not do for Welsh citizenship and history but that it will exacerbate the already significant difference between schools in affluent areas and schools that are not. Wales needs less difference between its schools, not more.

Martin Johnes is Professor of History at Swansea University.

This essay was first published in the Welsh Agenda (2020).

For more analysis of history and the Curriculum for Wales see this essay.

Getting ready to study history at university

Students starting history degrees in 2020 will be in unusual positions. It will be six months since they were last in a classroom. Some are worrying that not taking A Level exams will hold back their transition to university. This short blog is some suggestions of things students can do to help prepare.

Reading

In many ways, reading anything is preparing for university. Being comfortable with spending a lot of time in a book is important. Reading novels is a great way to both develop this skill and to start thinking about the past.

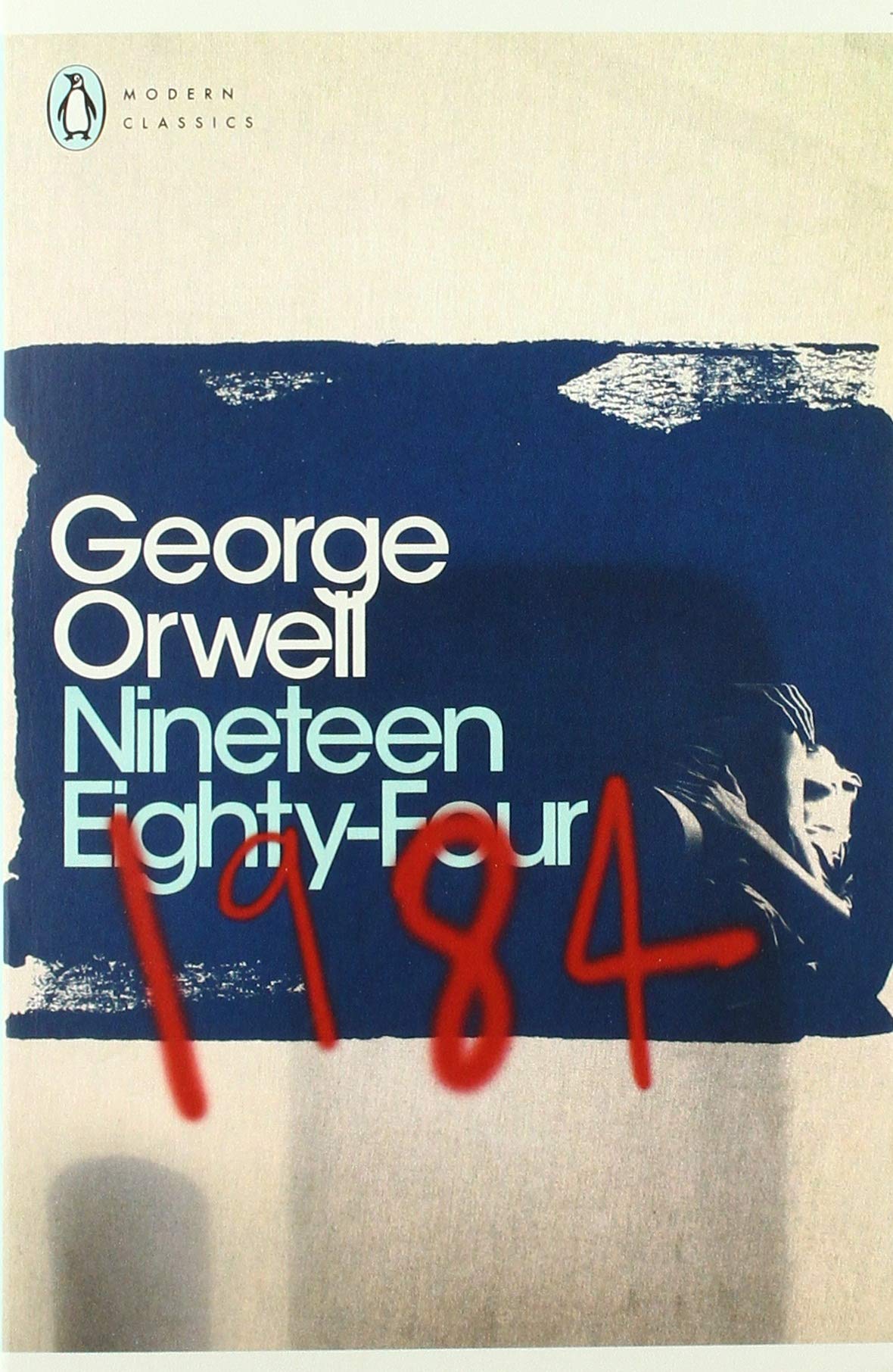

One book that everyone interested in the history of the modern world should read is George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949). Quite simply, it is one of the most (or perhaps the most) important novels ever written. It is about how power operates, and the role of history and knowledge in that. Its observations on oppression, privacy, freedom and what we now call fake news are very pertinent for the present day too. It also reminds us of how much fear for the future there was after the Second World War.

One book that everyone interested in the history of the modern world should read is George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949). Quite simply, it is one of the most (or perhaps the most) important novels ever written. It is about how power operates, and the role of history and knowledge in that. Its observations on oppression, privacy, freedom and what we now call fake news are very pertinent for the present day too. It also reminds us of how much fear for the future there was after the Second World War.

Podcasts

There are a vast amount of good historical podcasts out there. They are not dissimilar to lectures and are thus an excellent way of getting used to listening historians talking about subjects at length.

The National Archives have many that are very useful, partly because they often talk about the sources that history is based on. Here are a few particularly useful ones for the Modern British history. They will help you think about how varied history can be but also how we can assess and judge the past.

- Did militancy help or hinder the fight for the women’s franchise? https://media.nationalarchives.gov.uk/index.php/suffrage-100-militancy-help-hinder-fight-franchise/

- Blindness in Victorian Britain https://media.nationalarchives.gov.uk/index.php/blindness-victorian-britain/

- Shell-Shocked Britain: Understanding the lasting trauma of the First World War https://media.nationalarchives.gov.uk/index.php/shell-shocked-britain-understanding-lasting-trauma-first-world-war/

- England ’66: the best of times? https://media.nationalarchives.gov.uk/index.php/england-66-best-times/

Films about the past

Historians can be sniffy about their accuracy but historical movies really matter because they reach audiences far in excess of anything an actual historian ever writes.

Watching a variety of films on the same topic can be a very useful historical task. It helps us understand the public understanding of the past and it also involves a skill that is central to studying history – history at university is not just about studying the past but also about comparing and evaluating the ways that past has been interpreted and understood.

A fascinating and moving film that captures one perspective on women’s history and the First World War is Testament of Youth (2014).

It’s based on a famous memoir by Vera Brittain and portrays the growing disillusionment with war that some people felt. Alongside the war poetry of Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves and others, the original book was part of a genre that has led some people to think that was how everyone felt about the war. This genre influenced later tragic portrayals of the Great War such as War Horse and even Blackadder goes Forth. In this view, the war was something futile.

The pride many soldiers felt in what they had done has been rather written out of depictions of the war. You can see it, however, in Peaky Blinders when characters discuss the war. Even the recent Wonder Woman film could be argued as having some historical worth for how it portrayed the First World War as a battle against evil. That is how many people saw it at the time. Sometimes historical insights can be found in curious places. It doesn’t matter what you watch as long as you don’t just accept it as true!

Films from the past

Rather than just watching films made about the past, it’s also useful to watch films made in that past. They bring it to life in a way the written word perhaps can’t. Of course, they are selective in what they depict but no source is ever without ‘bias’.

The 1940s was something of a golden era for British cinema and offers rich viewing. Millions Like Us (1943) was a propaganda film designed to encourage people to feel their sacrifices were important and shared by people across Britain. It’s a vivid portrayal of the home front, class and gender, or at least how the film makers wanted the home front, class and gender be seen. It’s well worth watching and thinking about how audiences during the war would have felt about it. Did they think they were being manipulated? Did the film feel true to them? Does propaganda need to be subtle to work?

You can watch it here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pNglGkEmYDE and read more about it here: http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/442138/index.html

Write and talk!

Whatever you watch or read, it’s worth writing something about it. Put your thoughts onto paper or screen. It doesn’t matter if it’s blog, a Facebook post, or a message to a friend. Writing helps give shape to your ideas. It develops confidence that what you think matters (and it does!). Studying history is all about interpretation. There aren’t right answers. So practice telling others what you think about stuff, whether it’s historical, political or personal.

At university (and in many jobs) you will have to write a lot so using the written word is a skill to develop but so too is talking. Discuss things with whoever you live with. Articulate and debate but remember to listen too. Listening to others is key to learning.

Conclusion

History degrees are not really about what you know but about how you think. They encourage you to be critical about what you read and watch and to think about how things compare and connect to each other. These skills matter in the world and will help you in all kinds of jobs.

Thus what really matters in getting ready for university is not learning about specific things from the past but keeping your brain active. Read, think, talk and write! Just do that and you will be fine.

Why sport is an important topic for historical study

First published in History Review, 40 (September 2001), 26-27.

It is a common refrain that the two dates in English history that everybody schoolboy knows are 1066 and 1966. One event had a profound impact on the course of history in the British Isles while the other was just a football match. Yet soccer, like many sports, can be so much more than simply a game. It may not be more important than life or death, as the Liverpool FC manager Bill Shankly once famously claimed, but it can be a window through which we can view society. When England won the World Cup in 1966, the nation as a whole was on a high. The Beatles were revolutionising popular music, the miniskirt was making London the fashion capital of the world, there was a popular and populist Labour government in power and the economy was on the up. England’s triumph at Wembley seemed to confirm a nation that had found its destiny again after the painful transition that followed World War II and the dissolution of the Empire. Since 1966, the World Cup win has become a symbol of a nostalgic nation trapped in past glories and trying to refind itself and its ‘rightful’ place in the world. The memory of the triumph may not last as long as William’s victory at Hastings but it remains a powerful illustration of the symbolic importance of sport and its place within English national identity.

Yet it is only relatively recently that sport has been appreciated as the stuff of serious history and even today it sometimes struggles for recognition in some of the more traditional echelons of the subject. Nonetheless, sport’s contribution to our understanding of history extends beyond both symbolic importance and entertaining, but essentially trivial, footnotes. Nor is sports history a matter of just looking at how sport reflects society. Sport itself is an active agent in the world we live in.

This is clear in sport’s close relationship with class. Definitions of social class are complex and the subject of much historiographical debate. Occupation alone is no longer thought to be an adequate explanation and historians have begun looking at culture’s role in shaping how people defined the class status of themselves and others. By the twentieth century participation in many sports could be demarcated along class lines. Rugby league owed its whole existence to the northern working class’s desire to be free from the amateurist ideals of the southern and middle-class rugby authorities. As such the sport came to represent part of working-class life in the north of England. Thus, like soccer, it helped define the class of those who played and watched it, both in their own eyes and those of onlookers. Other sports played similar roles in directly contributing to people’s understanding and experience eof class cultures. Golf in England, for example, was a sport of the middle class and its clubs were important social and business networks that conferred upon their members privilege and status within the local community.

Yet for the importance of class in society, sport also illustrates its limitations as a lens through which all aspects of history can be judged. As contemporaries were well aware, a successful sports team could bring together the classes in celebration of the achievements of their town or nation. Indeed, sport’s (at least temporary) ability to unite the local classes whilst dividing the wider masses made it the subject of Marxist derision and elite approval. This was clear in the 1920s when, amidst social and political unrest, large well-behaved and socially mixed football crowds were a reassuring sight to many.

It is only through addressing wider historical questions like class that sport can be accepted as part of the academic world. Sports history is now becoming a distinct subject in its own right complete with journals, conferences and even degree courses. Yet studying and writing about sports history is not always easy. It is often the case that learning about the mundane and everyday in history is more difficult that investigating the extraordinary. Sports history does not benefit from the large range of sources available to political or more conventional social historians. This has meant it is, perhaps overly, reliant on newspaper evidence. However much information has also be gleamed from oral evidence, company records of bankrupt clubs and the archives of teams, sports organisations, local schools and councils. Through such research we are now beginning to understand sport’s place in history.

Britain was the cradle of the sporting world. Through her Empire and trading links, British games and sports were taken across the globe. Football thus spread from the English public schools, where its first rules had been drawn up, to become the game of the European and South American working classes. After the English language, soccer is perhaps Britain’s most successful and important cultural export. Cricket became an imperial sport, not through a ruthless process of cultural implantation but the desire of the local elites to adopt the practices of their colonial overlords. The amateurist ideals of the modern Olympics were heavily influenced by the traditions of the British public schools. Even baseball, that most American of sports, has its roots in children’s games taken across the Atlantic by British settlers. Sport can not be ignored if we are to understand the global legacy of Britain’s former economic, political and cultural power and influence. Indeed, British fair play and her love of sport became part of how foreigners traditionally viewed these islands.

Even within Britain, sport has played an important part in shaping national identity. For the Welsh, Scottish and Irish, sport has played an important symbolic role in affirming their nationhood and equality with England. While the Scots and Welsh enjoyed cutting the English down to size at football and rugby, the Irish increasingly rejected these sports in favour of their own indigenous games which could be used to symbolise a separate, and non-British, cultural heritage. Cricket meanwhile encapsulated many of the ideals of English life: a rural, moral and civilised but competitive world where gentlemen (amateurs) and working men (professionals) played together but knew their respective and clearly demarcated places. Thus ‘it’s not cricket’ became a description in everyday speech of anything that was ‘not right’.

For women sport has been both a source of inequality and liberation. This is aptly illustrated by the fortunes of women’s football during and after World War I. The football teams made of factory and munitions girls were just one example of the new social and occupational opportunities that women enjoyed with so many men away at the front. Yet after the war, just as women found themselves encouraged to leave their jobs and return to home and duty, the Football Association grew worried at the popularity of women’s football and banned its playing at professional stadiums. The sport collapsed although its brief flowering had given its participants a brief opportunity for physical liberation.

The historian Jack Williams pointed out that more people may have attended religious services or the pictures but no single church or cinema could boast as many as attendees as a professional football match. As such, sport was an integral element of urban life across Britain. History must strive to capture what was important to the people who lived it. Sport, of course, does not matter to everyone in society either today or in the past. But the fact that it has been an important part of many people’s lives is reason alone to justify its historical study.

A brief history of sport in the UK

First published in D. Levinsen and K. Christensen (eds.), Encyclopaedia of World Sport, Great Barrington, USA: Berkshire Publishing, 2005.

The United Kingdom was the birthplace of modern sport. From the drawing up of rules to the development of sporting philosophies, Britons have played a major role in shaping sport as the world knows it today. This role meant that British sport was overly insular and confident in its early days, while its post-1945 history was marked by doubts and crises as the nation realised that the rest of world had moved on, a situation that mirrored the UK’s wider crisis of confidence in a post-imperial world.

Pre-industrial sports

Pre-industrial sport in Britain resembled those in much of Europe. It was not a clearly demarcated activity but rather part of a communal festive culture that saw people congregate to celebrate high days and eat, drink, gamble and play. The sports of the people reflected their lives: they were rough, proud and highly localized. Rules were unwritten and based on customs and informal agreements that varied from place to place according to local oral traditions. ‘Folk’ football was one of the most common and popular examples of sport. It had existed in different forms across England and Wales since at least medieval times, but it resembled a mêlée more than its modern descendant. Traditional boundaries within rural society were celebrated within such games, with contests between parishes, young and old and married and unmarried. Other sports played at communal festivals included running races and traditional feats of strength such as lifting or throwing rocks.

The physicality of pre- and early-industrial Britain was also reflected and celebrated in bareknuckle prize fighting, although this widespread sport could not always be clearly distinguished from public drunken brawls. The brutality of life was further evident in the popularity of animal sports. Bull baiting and cock fighting were amongst the most popular but such recreations increasingly came under attack in the middle of the nineteenth century from middle-class moralists. The foxhunting of the upper class was not attacked, suggesting that the crusades owed something to concerns about the turbulent behaviour of the workers rather than just the suffering of animals.

The attacks on animal sports were part of a wider process of modernization that saw Britain transformed into the industrial workshop of the world. Urbanization, railways, factories, mills and mines saw Britain transformed, economically, environmentally and psychologically. Modern sport was forged within this heady mix of breakneck change; new ways of working and living brought new ways of playing. As well as the assaults on animal sports, folk football was attacked in towns because it disrupted trade and the general orderliness of the increasingly regimented world that industry was creating. Bareknuckle fighting too was attacked as a threatening symbol of a violent working class that unsettled an establishment already worried by the rise of political demands from the workers.

There was, of course, much continuity between the worlds of pre-industrial sport and the commercialised and codified games that emerged towards the end of the late nineteenth century. Cock fighting and prizefighting, for example, survived the attempts to outlaw them, but left the centres of towns for quiet rural spots or pubs and back streets that were away from the surveillance of middle-class authorities. ‘Folk’ football too lived on, although apparently on a smaller scale that was less orientated around traditional holidays and community celebrations. Its survival in this form surely underpinned the speed with which the codified form that emerged from the public schools was taken up by the masses across Britain.

The emergence of modern sport

Whilst forms of football were on the decline in mid-nineteenth century Britain, they were actually being adopted in the country’s public schools, as a means of controlling the boys and building their character, both as individual leaders and socially-useful team players. Underpinning the values that football was thought to cultivate were ideas of masculinity and religious conviction. Muscular Christianity deemed that men should be chivalrous and champions of the weak but also physically strong and robust. The belief that such qualities would create the right sort of men to lead the British Empire meant that a cult of athleticism, whose importance ran far deeper than mere play, developed within the English public schools.

Such traditions found a natural extension in the universities. It was here, particularly at Cambridge, that much of the impetus for common sets of rules developed in order to allow boys from different public schools to play together. It was from such beginnings that the moves towards codification of rules and the establishment of governing bodies mostly sprang. Most famously, representatives of leading London football clubs, including former public schoolboys, met in London in 1863 to establish a common code of rules for football and form the Football Association to govern the game.

With rules and a governing body behind them, former public schoolboys went out into the world, taking their games with them. Not only did this encourage the diffusion of sport outside British shores but it also led to modern sport being taken to the masses by a paternal elite who partly sought to better the health and morals of the masses, not least because of fears of national decline. Games like soccer and rugby were well-suited to urban, industrial communities, requiring only limited time and space and they very quickly developed in popularity amongst the working classes across Britain during the late nineteenth century. Such developments created an apparent homogenization of sports culture across Britain but there were distinct local variations. Knurr-and-spell and hurling, for example, enjoyed some popularity in the north of England and Scottish highlands respectively. Such traditional games furthered the continuity between pre-industrial and industrial sport but even they had to develop modern organisations and sets of rules to survive.

Modern British sport was not entirely rooted in the public schools and their spheres of influence. In Sheffield, for example, there were independent attempts to draw up sets of rules for football. Even amongst the southern middle classes, there developed popular sports, such as tennis, whose origins lay elsewhere. Golf could trace its written rules back into the eighteenth century Scotland but it was not until the wider sporting revolution and mania of the late nineteenth century that the sport’s popularity exploded amongst the British middle classes. Cricket was another sport whose written rules were drawn up in the eighteenth century and thus predate the public-school cult of athleticism.

Professionalism in cricket also dated back to the eighteenth century but as the phenomenon developed in other sports in the late nineteenth century, it, like other sports, developed an obsession with amateurism that was closely allied to the public-school ethos of fair play and playing for the sake of the game. Above all, amateurism was about projecting social position in a period of social change and mobility. To be an amateur in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain was to not need to be paid to play. Thus in cricket, where amateurs and professionals often played in the same team, social distinction was preserved through the use of different changing rooms, different ways of writing names and initially requiring professionals to labour with bowling and even menial tasks such as cleaning the kit. Yet, despite the snobbery that underpinned amateurism there was a general reluctance in most sports to impose explicit class-based restrictions on participation, though the Amateur Rowing Association was a notable exception. Furthermore, the reality of amateurism did not always match the rhetoric. Nowhere was this clearer than in the case of cricketer W. G. Grace (1848-1915). Undoubtedly the most famous sportsman of the Victorian era, Grace was a doctor and a gentleman but he was also supremely competitive and certainly not above gamesmanship and demanding excessively generous expenses.

It was in rugby and soccer that the issue of professionalism became most controversial. The growth of socially-mixed northern teams led to broken-time payments, where working men were compensated for missing work in order to play. Such payments however not only offended the amateurist principles of some of the elite, but they also threatened to take power away from the middle classes, both on and off the playing field. In soccer, professionalism was sanctioned in 1885 in order to ensure the middle-class Football Association retained control of the game, but it was soon tempered with severe controls on players’ freedom to move clubs and be paid what a free market might allow. Such tensions, fuelled by north-south rivalries, led rugby to split into two codes (which later became known as league and union) in 1895. Rugby league became a sport whose whole existence and identity was closely interwoven with ideas of working-class identity in northern England.

Watching and playing

Clubs could afford to pay players because soccer and rugby had become something that people watched as well as played. This owed much to the establishment of cup competitions, which, fed by civic and regional rivalries, gave some purpose and excitement to matches. In the industrial north of England, the growing crowds began to be charged for the privilege of watching and hosted in purpose-built grounds. Such crowds worried the class prejudices of social onlookers, who complained about the drinking, gambling and partisanship of supporters, as well as the impact on the nation’s health of a population that spent its free time watching rather than playing.

When soccer played on after the outbreak of war in 1914 the reputation of professional sport plummeted amongst the middle classes. Nonetheless, sport was to play an important role in maintaining troop morale at the front. In the aftermath of the Great War spectator sport reached new heights of popularity. The largest league games in soccer could attract as many as 60,000; yet, beyond drinking and gambling, disorder was rare. This led the sport to be celebrated as a symbol of the general orderliness and good nature of the British working class at a time of political and social unrest at home and abroad.

For spectators professional sport offered an exciting communal experience, where the spheres of home and work could be forgotten in the company of one’s peers. As such, crowds at professional soccer and rugby league became overwhelmingly masculine enclaves that fed a shared sense of community, and perhaps even class, identities. Sport’s ability to promote civic identity was underpinned not by the players, who being professional were transient, but by the supporters and the club sharing the name of its town or city.

Yet these crowds were not actually representative of such civic communities. Professional sport was mostly watched by male skilled workers, with only a sprinkling of women and the middle classes. The unemployed and unskilled workers were, by and large, excluded by their own poverty and the relative expense of entry prices. Consequently, as unemployment rocketed in parts of Britain during the inter-war depression, professional sport suffered; some clubs in the hardest hit industrial regions actually went bankrupt. Working-class women meanwhile were excluded from professional sport by the constraints of both time and money. Even the skilled workers did not show an uncritical loyalty to their local teams. Professional sport was ultimately entertainment and people exercised judgement over what was worth spending their limited wages on seeing.

Men played as well as watched and the towns of Britain boasted a plethora of different sports, from waterpolo in the public baths, to pigeon races from allotments, and quoits in fields behind pubs. Darts, dominoes and billiards flourished inside pubs and clubs. Space was, of course, a key requirement of sport but it was at a premium and the land that was available was heavily used. For all the excitement that sport enabled men and women to add to their lives, they were still constrained by the wider structures of economic power.

Working-class sport could not be divorced from the character of working-class culture. Local sport was thus intensely competitive and often very physical. In both football codes, bodies and fists were hurled through the mud, cinders and sawdust of the rough pitches that were built on parks, farmland and even mountainsides. But, win or lose, for many men and boys, playing sport was a source of considerable physical and emotional reward. For many youths, giving and taking such knocks was part of a wider process of socialization: playing sport was an experience that helped teach them what it meant to be a man. Similarly, working-class sporting heroes reflected the values and interests of the audience; they were tough, skilled and attached to their working-class roots.

Cricket was the national sport of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century England, in that its following was not limited to one class or region. Matches in urban working-class districts may have lacked the pressed white flannels or neat green wickets of a test match at Lord’s but they shared the same intricacy and subtlety of play. The contest between the skill and speed of the bowler and the technique and bravery of the batsmen was one familiar to both working-class boys and upper-class gentlemen. Cricket’s popularity owed something to the rural image of England that it encapsulated. Cricket on the village green was an evocative and emotive image, employed even by a prime minister at the end of the twentieth century. Yet, from the English elite, cricket spread not only to the masses of the cities but also the four corners of the vast British Empire, where it enabled the colonies to both celebrate imperial links with the motherland and also take considerable pride in putting the English in their place.

Like cricket, horseracing had been organised since the eighteenth century and was followed by all classes from Lords to commoners. Gambling was at the core of its attraction and a flutter on the horses was extremely popular, despite its illegality (until 1963) when the bet was placed in cash and outside the racecourse. As with soccer, the sporting press offered form guides and was studied closely, with elaborate schemes being developed to predict a winner. The racecourse itself was often rather disreputable, with the sporting entertainment on offer to its large crowds being supplemented by beer, sideshows and, in the nineteenth century, prostitutes. It provided the middle classes with an opportunity to (mis)behave in a manner that would be impossible in wider respectable society.

Respectability did matter on the golf course and in the clubhouse. Although it had something of a working-class following, especially in Scotland, golf was a sport of the middle class and its clubs were important social and business networks that conferred privilege and status within the local community upon their mostly male membership. Tennis too had both a middle-class profile and a social importance that often marginalized actually playing the game. Like archery and croquet before it, for the urban middle class of the early twentieth century, the tennis club was an opportunity to meet and flirt with members of the opposite sex of the ‘right sort’. In such ways, sport became an important part of the lives of a middle class that was increasingly otherwise socially isolated in the new suburbs.

As in the rest of Europe, the shadow of war was hanging over the suburbs by the 1930s. In such an atmosphere, sport itself became to be increasingly political. The England soccer team were even told by the appeasing Foreign Office to give the Nazi salute when playing an international in Berlin in 1938. The threat from Germany also led to renewed investment in playing fields, as concerns resurfaced about the fitness of a nation on the brink of war. Unlike in the First World War, sport was fully promoted during the 1939-45 conflict, as an improver of spirits and bodies for civilians and troops alike.

Britain finished the Second World War victorious but physically and economically exhausted. In the austerity that marked the late 1940s, sport was one readily obtainable relief and, encouraged by growing radio coverage, soccer, rugby, cricket and boxing enjoyed huge crowds. There were also large crowds at the 1948 Olympics, which London stepped in to host with the hope that the games would rejuvenate tourism and help put some colour into the post-war austerity. The games were an organisational success and even made a profit, the last Olympics to do so until 1984. After leaning towards isolationalism in both politics and sport during the inter-war years, the post-war period saw a new awareness in Britain of its relationship with the rest of the world. With the Empire being dissolved, international competitions like the Olympics began to matter more as indicators of national vitality. The conquest of Everest in 1953 offered some optimism and confidence for the future but soccer, Britain and the world’s most popular game, was not reassuring for its inventors. England’s first forays into the World Cup were far from successful and indicated that the country’s loss of global power was not confined to the political sphere.

The television era

As economic prosperity returned in the 1950s, spectator sport suffered a downturn in popularity, as it competed against the lure of shopping, cars and increased domestic comforts, of which television was one of the most alluring. Such alternatives were particularly appealing to older men and thus the 1960s seemed to witness crowds, in soccer at least, become younger. One consequence was the rise of a youthful football fan culture that utilised humorous but obscene and aggressive chants and promoted fighting between rival supporters. The media spotlight, increasingly looking for sensational stories from across sport, amplified the hooligan problem but from the late 1960s to 1980s it was a genuine and widespread subculture that drew more upon the thrill of limited violence than any sense of a disempowered youth rebelling against the world.

Initially, there was only limited sport shown on television and many sporting authorities, not least soccer, feared that coverage would kill live audiences. Yet others, like golf and horseracing, saw television as an opportunity to develop their popularity and thus courted its coverage. The growth of televised sport was therefore sporadic; in the 1950s and 60s it was too often limited to edited highlights or live coverage of only the biggest events in the sporting calendar.

Yet televised sport was to become hugely popular and influential. In the 1960s, coverage of the Olympics and the 1966 World Cup won mass audiences and turned the events into shared celebrations of a global sporting culture. Wimbledon became, for most people, a television event rather than a live tennis championship, while rugby league became inextricably linked to the northern tones of commentator Eddie Waring. By the 1970s, television coverage had also helped turn rugby union’s Five Nations Championship into a very popular competition that transcended the sport’s middle-class English foundations.

Television also opened up the opportunities to commercially utilise sport, not least through sponsorship. Athletics was one sport where television and sponsorship increased its profile and popularity, but this also created tensions between the amateurist traditions of the administrators and the commercial demands of the stars. Other sports suffered similar tensions and responded by either slowly becoming explicitly commercial, as in the case of professional golf, or turning a blind eye to transgressions of the amateur code as in the case in athletics and parts of rugby union. Yet, ultimately, money talked and amateurism gave way to commercial pressures across senior sport.

The changes television was starting to bring about could be radical. Cricket proved surprisingly willing to embrace change and even introduced a one-day Sunday League as early as 1967, as it searched for a more accessible and exciting one-day format to supplement the waning four-day county game. After the invention of colour television, snooker was televised from the late 1960s and the sport was transformed from the realm of smoky pubs to something resembling a national craze. The relatively static nature of the game meant that it was cheap to broadcast and conducive to dramatic close ups. Snooker also had the characters and personalities that the media was increasing seeking in its coverage of sport.

The real commercial boost from television came in the 1990s, with the development of satellite television. Soccer was seen as the key to securing an audience for the new medium. Rupert’s Murdoch’s Sky thus spent enormous sums on securing and then keeping the rights to televise the game’s senior division. After the 1980s – when hooliganism and the fatal horrors of disasters at Bradford, Heysel and Hillsborough had seen English football sink to its lowest ebbs of popularity and standing – Sky’s millions enabled the game’s upper echelons to reinvent itself in the 1990s. New all-seater stadia (enforced by the government to avoid a repeat of the 96 deaths at Hillsborough in 1989) made watching soccer both safer and more sanitised, an influx of talented foreign players raised standards of play, while a more cynical and overtly commercial edge developed amongst the game’s owners and administrators. Players were the main beneficiaries as their profile, wages and sponsorship opportunities rapidly escalated in the now hugely fashionable and celebrity-conscious game. David Beckham epitomised this transition, with his pop-star wife, countless sponsorship deals and media-frenzied private life. Fans meanwhile could watch more soccer than ever on television but actually attending matches was becoming extortionately expensive. Other sports were keen to follow soccer’s example. Rugby league became Super League, its teams gained American-style epithets and the sport even moved from winter to the less crowded television schedules of summer. Rugby union, fearing being left behind, suddenly abandoned its strongly amateur heritage and turned professional in 1995, a move that was to bring it as many financial headaches as rewards.

Identities and inequalities

In the second half of the twentieth century, spectator sport and television may have become interwoven in a relationship built on money, but participatory sport did not die out, although it too became part of a leisure industry that sold everything from training shoes to personal gyms. As throughout the twentieth century, participation remained skewed by class. The wealthier appeared not only more able to afford to play sport but they also appeared more interested in doing so. The foundations and boundaries of the British class system were becoming increasingly blurred and the diminishing class associations of the most popular sports reflected that. Yet historical legacies and financial requirements still meant that equestrian sport remained beyond the reach and often tastes of the masses, whilst activities such as boxing and darts remained closely allied to working-class culture. Success at such sports could take performers out of their working-class origins but this did not end the cultural resonances of the sports that had been built up over a century.

Nor were the gender biases of sport ended by the equal opportunities ethos of the late twentieth century. Playing and watching sport remained far more popular amongst men, despite the significant advances made in female participation rates and the profile of some leading sportswomen. Olympic athletes like Denise Lewis or Kelly Holmes may have ventured into the celebrity world of sports stardom but, at the start of the twenty-first century, women are still on the margins of sport, in terms of numbers, profile and culture.

Athletes from Britain’s ethnic minorities have, however, broken through into the mainstream of nearly all the country’s most popular sports. In the early twentieth century, there had been occasional black athletes in boxing and soccer in particular, but it was the 1970s that saw British sport become genuinely ethnically-mixed, when the sons of the first generation of large-scale immigration reached adulthood. By the twenty-first century, England’s national teams had even had black and Asian captains in soccer and cricket respectively. Such achievements were not simply symbolic but also encouraged a degree of wider racial integration in national culture. Yet sport has also been, and continues to be, the site of explicit racism (notably in the form of soccer chants) and more subtle preconceptions about the playing abilities of different ethnic groups. Such prejudices partly explain why few professional soccer players have emerged from the UK’s large Asian population.

While little sustained media attention was ever devoted to sporting inequalities based on class, gender or ethnicity, nationhood was a topic of widespread popular interest. When in 1999 Chelsea Football Club fielded a team that did not include a single British player, there were debates about globalization’s potential impact on the future success of British international sides. Sport had always played an important role in shaping national identity within the United Kingdom. For the Welsh, Scottish and Irish, it had an important symbolic role in affirming their nationhood and equality with England. While the Scots and Welsh enjoyed cutting the English down to size at football and rugby, the Irish increasingly rejected these sports in favour of their own indigenous games, such as Gaelic football and hurling, which could be used to symbolise a separate, and non-British, cultural heritage.

Doing a dissertation on modern Welsh history

Some brief advice to help you choose a dissertation topic

Your dissertation needs to be something you find interesting and something which you can practically do. The latter means something not too big and something where the sources are accessible.

One advantage of doing a Welsh subject is that the archives are close to where you are studying. The Richard Burton Archives are in our library. West Glamorgan archives are in the civic centre. Cardiff has the Glamorgan Archives.

There are also a wealth of online sources for modern Wales. You can find a list here.

You need to think about what kind of sources you want to use. Do you want to go to an archive? Do you want to use online newspapers? The latter can mean wading through lots and lots of articles if your topic is thematic. They are more accessible than an archive but can take longer.

Possible approaches:

Pick an event. The dissertation would be along the lines of what happened, why did it happen, why did it matter. You would be telling the story but in an analytical way.

The event needs to be small enough to be told in detail. The Second World War is far too big! Think more something like a specific election, battle, disaster etc. Don’t worry about whether anyone has written about it before. The primary sources will tell you the details. You can get the analytical ideas from looking at similar events or the same event in another place.

For example, the 1945 general election is too big and well known but you could do the 1945 general election in Swansea. The newspapers and local political records give you primary sources. The writing on the election more generally gives you the ideas and framework. The dissertation becomes, essentially, historians have said X about the election, is this true of the election in Swansea?

A big advantage of an event is that you know the date of it and thus it’s easy to find in the newspapers!

Pick a theme and apply it to a place. Again, the more specific the better. Welsh women’s history is too big but marriage in Wales between the wars is not. Pubs is too big but pubs in Victorian Swansea is not. Education in Wales is too big but schools in Swansea during the First World War is a great topic. Again, the general literature will give you the ideas and the primary material give you the examples to test those ideas with. No one needs to have written about your specific theme. In fact, that helps you be original. For example, no one has written about pubs in Victorian Swansea but that means you’re being original. They have written about pubs in Britain so you will have plenty to read to and ideas to test and guide your research.

Some other example dissertation topics to illustrate approaches:

The Welsh language in a street or village. You look at the census returns for a small area for 1891, 1901 and 1911 and work out how spoke Welsh, their jobs, their family circumstances and how this changed over time. Then you think about what this tells us about the changing nature of the language and how it fits with historians’ arguments about this. You would also read about the history of the village, or the town that the street was in.

Motoring in Edwardian Wales. You look through the newspapers for articles that use the terms motoring or motor car. There will be quite a lot! You see that historians have motoring have argued it was seen as a sign of modernity, a nuisance and a legal problem. You find examples of each from Wales and see if you agree with the historians’ arguments. You might have a chapter on each. If other themes jump out at you from your reading of the articles you could have sections on those too. Because councils get involved you might look at their records too. You see court cases so a good student might hunt down police records too.

Digital resources on Welsh history 1847-1947

This probably duplicates info already on Blackboard / Canvas but hopefully it helps with your essays when library access might be reduced. It should be used in conjunction with the guide to online historical sources produced by the library. The list below is more Wales-specific and focuses on what is useful for the Welsh Century module.

There is a review of the academic historiography of modern Wales here. You’ll need to use your Swansea log-in. It’s a bit dated now but does offer an introduction that should give you ideas. There is another version of the same essay here which does not require a log in.

Historical Welsh newspapers

Access to a large number of local newspapers from Wales from the pre 1919 period. https://newspapers.library.wales/

Welsh journals and periodicals

This is full-text versions of journals, magazines and periodical from the eighteenth century until the 21st century. It will thus give you access to primary and secondary sources and can be searched by name, place, word etc. https://journals.library.wales/

Dictionary of Welsh Biography

Short biographies of eminent and sometimes obscure figures in Welsh history. If you want to find out about individuals you should also look at the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Swansea log-in required).

Historical statistics

The Digest of Welsh Historical Statistics 1700-1974

Moving Pictures

The British Film Institute has a variety of different films about Wales. The collection includes home movies and factual films.

Newsreels were news fims broadcast at the cinema before the main picture. You can access newsreel reports from between the wars here. Just search for Wales.

Welsh History Review

This is the leading journal for academic work on Welsh history. Digital copies are free from 1967 to 2002. If you are looking for a specific article and volume you can access them here. If you are searching for a theme or key word, then use this search page and enter Welsh History Review into the publication title box.

For issues after 2002, you need to use this database. You will need to sign in using your Swansea login details.

Llafur

Llafur is the other academic journal dedicated to general Welsh history.Digital copies are free from 1972 to 2004. If you are looking for a specific article and volume you can access them here. If you are searching for a theme or key word, then use this search page and enter Llafur into the publication title box Issues after 2002 are not online.

This is an online repository for historical images and some documents. The content is quite eclectic but it is full of rich material and worth searching.

Contains full text versions of many nineteenth-century publications including the infamous Blue Books. Worth playing around.

History of the Welsh language

- An important essay about the early history of the Welsh language question on the census.

- 1891 census report on languages in Wales

- 1901 census report on languages in Wales

- 1911 census report on languages in Wales

- 1921 census report on language in Wales

- Overview of how the census question on Welsh has changed and its accuracy

Wales and War

- Cymru 1914: the Welsh experience of the First World War A digital collection of primary sources on Wales and the First World War

- Historical resources on peace activism in Wales http://www.walesforpeace.org/wfp/index.html

- Green Mountain, Black Mountain (1942). A Second World War propaganda film written by Dylan Thomas that offers a vivid picture of Wales.

- Martin Johnes, Welshness, Welsh Soldiers and the Second World War. Academic chapter.

- Some short online essays by me on Wales and the Second World War

- Daily Life During World War II (BBC Wales)

- Evacuation and Wales in World War II (BBC Wales)

- Bombing raids in Wales (BBC Wales)

- Women in World War II (BBC Wales)

- The coal industry in World War II (BBC Wales)

- Welsh identity during the Second World War (BBC Wales)

- Swansea’s Blitz (Click on Wales)

- You should also, of course, also consider the British historiography since this was a period when there were very clear UK-wide trends. An excellent academic introduction for the Second World War can be found here.

Women’s history

- Resources from the National Museum looking at 1900-1918

- Welsh Women’s Archive Includes material on women in the First World War.

- A BBC podcast where Dr Stephanie Ward discusses gender in modern Welsh history

Politics

- Labour Party manifestos

- A BBC podcast where Dr Daryl Leeworthy discusses the politics of mining communities and what the Labour Party achieved

- Hansard: transcriptions of Parliamentary debates

- Election statistics (1918-)

- British Cartoon Archive (University of Kent) http://library.kent.ac.uk/cartoons/ World’s largest archive of (newspaper) cartoons.

- Plaid Cymru History– lots of phamplets and other resources

- Cabinet papers from the British government. What happened in Wales was shaped by decisions made in Westminster…

Maps

Explore historic maps from Wales and the UK here.

Television documentaries

Episode 2 of Wales: England’s Colony? (2019) Presented by yours truly, it explores the relationship between Wales and England in the modern period.

Episode 4 of The Story of Wales (2012). An overview of the industrial revolution and its impact on Wales.

Episode 5 of The Story of Wales (2012). An overview of industrial and modern Welsh society. Covers much of the ground we have looked at in The Welsh Century.

Saunders Lewis (1992). A documentary about one of the founders of Plaid Cymru.

The Dragon has two Tongues. This was a 1980s documentary that debated Welsh history. ITV have not allowed it to be put online but these extracts offer some sense of its overall debate about the nature of Wales’s past.

The stories that bind us: history and the new curriculum

This weekend I attended an excellent event put on by the Cardiff Story museum about the 1919 race riots. The speakers included artists and activists from the Butetown community that was the victim of the 1919 racist attacks. There was a clear desire among both speakers and the audience that the riots be remembered and that the community be allowed to tell its own history.

Theatre events, poetry and art are allowing the riots to be remembered now, but ensuring the memory lives on beyond its centenary is less straightforward. There was a clear ambition voiced at the event to see the riots, and black history more generally, placed on the Welsh national curriculum.

The national curriculum in Wales is currently undergoing a radical redesign but it will be based around specific skills rather than specific knowledge. Thus in history there will be no requirement that any particular event or person is taught. Similarly, in English and Welsh literature, there will be no poet or novelist who is required reading.

Teachers and schools already have some choice about what they teach but now they will be given free rein to use whatever content they like to meet the curriculum’s overall requirements of ensuring pupils are

- informed citizens of Wales and the world

- ambitious and capable learners

- enterprising and creative contributors to society

- healthy and confident individuals.

The curriculum also requires that the Welsh context in which pupils live should be central to all these ambitions.

Teaching pupils about the race riots of 1919 would certainly fit with the curriculum’s ambitions and there would be nothing to stop schools using it as a way of both teaching about the past and encouraging thinking about the dynamics of race today. However, the new curriculum will not allow this to be a requirement. If it happens, it will have to be the choice of individual teachers and schools.

As someone in the audience at the 1919 event stated, this means that there is no guarantee that children will learn about the riots and the racism they involved. It may be, it was suggested, that some white teachers will not see ensuring such things are taught as important.

The same fears exist among those who want every child to learn about other specific events that are central to the history of Wales. There is no guarantee that any pupil will learn about medieval conquest, the flooding of Tryweryn, the Second World War, the struggles for civil rights, or the rise of democracy. Some children will learn about all these things but future citizens’ knowledge of history could vary significantly according to which school they attend.

This has implications for the very nature of Welsh society. The curriculum is intended to foster a sense of Welsh citizenship and to put that in a global context. The question is whether that can be achieved when every child is learning about Wales through different sets of knowledge.

Wales is a diverse place and Welshness means many different things. A curriculum that reflects this, and a nation that is comfortable with a plurality of knowledge, is a mature one. A curriculum that demands every child learn the same ‘national story’ is perhaps something that only a country unsure of itself would produce. Such a story would also inevitably lead to considerable controversy about what it should include. And that is before any consideration of how events should be interpreted.

No historian would argue that there is a single simple Welsh story that could be taught. The past is both vast and complex. Deciding what matters is a political decision. So, too, is explaining why something matters. Giving power to schools and teachers does not overcome that but it does at least free the curriculum from the kind of government interference Michael Gove tried to enact in England in 2013 with his plans for a revised patriotic history curriculum.

Yet teachers are political too, and they do not operate in value-free environments. Their own interests and experiences will influence what they decide to teach. They will, inevitably, reproduce some of the existing outlooks instilled in them by their own education.

Thus those who hope the new curriculum will lead to a flourishing of Welsh history may find it doesn’t because of the existing lack of Welsh history taught in schools and universities. Those who hope it will lead to more teaching about the diversity of Wales may find it does not because that diversity is so often invisible in existing practices. Where teachers come from, where they go to university and who they are will have profound influences on the evolution of the new curriculum.

The freedom the curriculum gives teachers is both its strength and its weakness. It should allow teachers to tell the stories of their own communities and to give them and their pupils a sense of ownership over those histories. It is certainly a recognition of teachers’ professional standing and experience. It should give them the opportunity to innovate and develop exciting programmes that inspire our children.

But it will also be up against the challenges of time and resource that teachers face. It will be up against the real socio-economic inequalities which exist and which challenge teachers in their daily working lives. It will be easier to develop innovative curricula in schools where teachers are not dealing with the extra demands of kids who have missed breakfast or who have difficult home lives. The very real danger of the new curriculum is that it will exacerbate the already significant difference between schools in affluent areas and schools that are not.

The age of devolution has seen too many excellent policies flounder because of how they were (or were not) implemented. There will be an onus on government to ensure that schools are not cast adrift and left to work out things for themselves. They need support and, I suspect, a whole host of exemplar programmes to show the curriculum can work in practice. If those exemplars are of high enough quality, schools will adopt them. It is through such exemplars and resources that there is the best opportunity to ensure the important themes and events in our history are taught in our schools.

In Game of Thrones, Tyrion Lannister claims that it is stories that bind people together. He is right. History’s stories can inspire, empower, liberate and unite us. It is not necessary that everyone knows all the stories. It will be impossible to agree which stories matter most and how they should be taught. There is nothing wrong with empowering the storytellers to make those decisions. This makes political and pedagogical sense.

But I also cannot help worrying that the new curriculum might further fragment society. Despite my belief that all histories are equally valid, I cannot escape a nagging doubt that it would be wrong if children did not what know the basics of what happened in the Second World War or that people of colour have a long and rich history in Wales. 1919 is a reminder of what can happen when societies are not bound together. It should not be forgotten.

The impact of the Second World War on the people of Wales and England up to 1951

Resource for WJEC History A Level Unit 1, Option 4

POLITICS, PEOPLE AND PROGRESS: WALES AND ENGLAND c.1880-1980

Debate the impact that the Second World War had on the people of Wales and England up to 1951

All wars have significant social and economic impacts but this is especially so in the case of the First and Second World Wars. Their impact was very different to previous European conflicts that Britain had been involved in because of their scale, the involvement of the civilian population, and the extended powers and actions of the state. Because the state operated at a British level, many of the war’s impacts did not differ between England and Wales. However, the war did heightened Welsh national consciousness, despite the power of popular and political Britishness. Yet this was actually an existing long-term process and many of the impacts of the war were a quickening of trends already taking place.

Conscription and the Armed Forces

Conscription was introduced for all British men between the ages of 18 and 41 from the outbreak of war. Some men were exempt because they were in ‘reserved occupations’ which were important for the war effort. This was particularly common in the south Wales valleys where the coal industry dominated employment. The scale of mobilisation meant it might be months before some men were actually called up. This added to the sense of the early months of the conflict as a ‘phoney war’, where little was happening.

By the end of the war, some 5 million British men and women were in uniform. Of these, perhaps 300,000 were Welsh, although there was never any attempt to come up with an official number. This in itself was a sign of how the war effort was perceived as a British one.

Only a minority of men in the armed forces actually saw combat. For those who did and survived, the experience could be frightening but it also often created a deep camaraderie and it was sometimes even seen as exhilarating. That camaraderie deepened the sense of loss felt when comrades were killed. Over the course of the war, almost 300,000 British members of the armed forces and merchant navy lost their lives. Estimates of the number of Welshmen killed are around 15,000.

Whatever their experience, service in the armed forces usually left a profound mark on men and women that stayed with them for the rest of their lives. For some it was a proud time when they had contributed to something that changed the world for better. Others, however, were frustrated at the routine, the discipline and the disruption it brought to their lives and plans.

The Home Front

The war affected every aspect of daily life, and not always in negative ways. Wages increased and unemployment virtually disappeared. But that was small compensation for the hardships and sacrifices everyone endured. Working hours grew longer, entertainments were curtailed, the blackout cast a gloom over the evenings and there were shortages of everything from food and clothes to beer and paper. People’s weariness with these hardships was as much a threat to popular morale as the very real physical dangers of war. 67,635 civilians were killed in air raids on Britain, 984 of whom were in Wales.

One hardship that touched everyone was rationing, although it was stoically accepted by most, no matter how much they grumbled. Wartime diets were limited in quantity and rather plain and tedious. Nonetheless, rationing and price controls meant much of the working class actually saw their diets improve after the interwar years of unemployment and poverty. The fact that rationing affected everyone also created a sense of shared sacrifice that cut across class lines. However eating at restaurants was not rationed at first, and thus those with money had access to more food, an example of how there was a more complex reality beneath the veneer of national unity.

The combination of everyday austerity, the worry over friends and family serving abroad, and, early in the war, the fear of invasion, meant that small pleasures like a pint, a dance, a film or a kiss became all the more important to people. The cinema, in particular, saw its position as the central pastime of the people enhanced. It also developed a new role as a medium of propaganda. A steady stream of films of varying quality tried to convince viewers of the righteousness of the British cause and the importance of everyone all pulling together in its pursuit. Audiences were not always impressed and there was a general skepticism about anything too overtly propaganda-like. Such things were felt unBritish and more appropriate for the fascist countries being fought.

Women

Propaganda encouraged women to join the war effort in factories, farms and the forces and they were conscripted to do so from 1942. Equally important was their role as mothers, housewives and volunteers, helping with everything from dealing with air raids and evacuees to cooking and cleaning for the troops. Indeed, during the war, there were more women in Britain who were housewives than there were in full-time paid employment.

The biggest demand for female labour came from the new munitions factories. In Wales the largest such factories were in Hirwaun, Glascoed and Bridgend which employed over 60,000 people between them, the majority of whom were women. There was patriotism in the factories and women were sustained by the knowledge they were doing something that contributed to victory. Factory work also paid well and many of the early volunteers were motivated by the desire to earn money. This was especially true for women from the south Wales valleys who had shouldered the burden of running a home during the inter-war years of mass unemployment.

Despite the extra money, the experience of working was not all positive. Leaving home could be traumatic, especially for Welsh-speakers sent to English factories. Munitions work could turn women’s hair and skin yellow. Factory hours were long, the commuting tedious, and the work itself monotonous. Many still had domestic commitments and finding time for shopping became a particular cause of complaint. The ‘land girls’, women sent to work on farms, also often endured a difficult war. Long hours, poor food, hard physical work and the isolation of rural farms were all common complaints.

Men were also not always happy with their women working. Some husbands could no longer expect dinner on the table when they got home. There was indignity among some miners when they discovered that they were earning less than their wives or daughters. There were also accusations that the children of factory workers were being fed from tins and not disciplined properly.

Coping with the problems of war work was made much easier by the camaraderie that existed in all spheres of employment. Female workers also had money to spend in a climate where the social rules on what women could do were changing. The cinema, the dance hall and even the pub were all important places where women could relax. To cope with the hardships and tragedies of war, many women adopted a philosophy of living for today, spending freely and worrying less about what others thought and what the future held. One result was, at least according to some disapproving voices, a slackening of sexual morals. What was certainly happening was that gender was no longer quite as constraining as it once had been, although the fact that not all approved showed the limits of this shift. Moreover, the post-war aspirations of most women remained overwhelmingly traditional: a nice home, a good husband and healthy children.

National identities

Many of the experiences of everyday life during the war crossed regional, cultural and class barriers in Britain and created a strong shared sense of purpose and experience. Rationing, bombing, conscription, the loss of a son or husband – all these trials and tribulations fell on rich and poor, Welsh and English alike. Money and social position still mattered in civilian life and the armed forces, but the sense of solidarity and mutual-interest across Britain was strong, even if it was not always matched by reality.

Central to the idea of the united British nation was the BBC. Its news service, prime ministerial broadcasts and comedies all attracted huge audiences and were key parts of the shared British wartime experience. However, there were still many, especially in rural Wales, without radios. There were also over 40,000 Welsh people who could not speak English. The BBC did broadcast some twenty minutes a day in Welsh. This helped ease some of the annoyance caused by the BBC broadcasters who sometimes spoke of England’s rather than Britain’s war.