A short video some Swansea University students made.

Category: popular culture

Goodbye, Mr Chips, modern education and the REF

Last night I watched a lovely 1939 film called Goodbye, Mr Chips. In it, an elderly teacher rallies against the Headmaster of the public school he has spent his career at:

I’ve seen the old traditions dying one by one. Grace, dignity, feeling for the past. All that matters here today is a fat banking account. You’re trying to run the school like a factory for turning out moneymaking machine-made snobs! You’ve raised the fees, and in the end the boys who really belong to Brookfield will be frozen out, frozen out. Modern methods, intensive training, poppycock! Give a boy a sense of humor and a sense of proportion and he’ll stand up to anything.

Historians more than anyone should be aware of the dangers of nostalgia but as universities spend the next few days pondering, proclaiming and panicking over the results of the Research Excellence Framework, it will be difficult not to think this is not what education should be about.

The Victorian public school system is hardly a model for what universities should be doing in the 21st century but Mr Chips understood that education is about far more than things that can be quantified, monetized and put into boxes or league tables.

Disco for the Eyes: NME’s review of Star Wars

I stumbled on this last week whilst reading through the NME’s incessant hatred of Christmas songs. The NME thought it was far too cool for its own good but this is unusually perceptive.

“Star Wars is the only movie I’ve ever seen which captures the unique feeling of reading comic books while stoned. … The ‘70s are a time of coping with psychic defeats and the deadening of our collective nerve ends, and Star Wars is an entertainment built around spectacle: it tickles, dazzles and delights the senses while leaving the intellect and the emotions as undisturbed as possible. Finally, it’s disco for the eyes.”

New Musical Express 24 December 1977

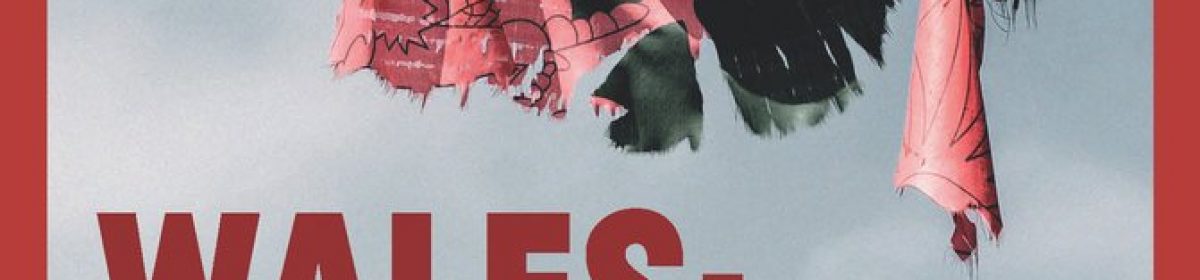

The Alarm: 1980s Wales in a Band

The Alarm sold 5 million records but they were never cool. Even in the early 1980s, when they were singing punkish rebellion songs like 68 Guns, the band never won the critical acclaim of the music press. Instead, they were derided as pretentious and inferior imitators of U2. Even their big hair was mocked.

The Alarm sold 5 million records but they were never cool. Even in the early 1980s, when they were singing punkish rebellion songs like 68 Guns, the band never won the critical acclaim of the music press. Instead, they were derided as pretentious and inferior imitators of U2. Even their big hair was mocked.

Perhaps it was just easier to be cool if you came from Dublin rather than Rhyl but even in Wales those who take their rock and pop music seriously have not accorded The Alarm much credit. Books on Welsh music history overlook or deride them (although David Owens’ Cerys, Catatonia and The Rise Of Welsh Pop is a notable exception). The contrasts with the feting and celebrations of the Manic Street Preachers could not be greater.

The Alarm released five studio albums between 1984 and 1991, although the name was revived by singer Mike Peters in 2000 and he continues to tour and record under it. Peters’ health problems and his continuing musical and charitable work mean that the band continue to have some profile in Wales at least. The derision that was sometimes aimed their way has faded but it has not been replaced with popular affection or admiration.

The Alarm, however, do deserve some recognition and even analysis. Music does not have to be original or innovative to say something and touch people and the Alarm did both. Their popularity alone means they deserve a mention in the contemporary history of Wales. But more than that, The Alarm also offer a window into wider trends in that history, not just in what they did but also in how they ran against contemporary currents.

The band’s early albums captured the anger and frustrations felt by so many young people in a period of mass unemployment. Most young people may not have been rioting or even been particularly politicized but there was a certainly a resentful sense that affluence and opportunity were not being equally shared out. As The Alarm sang in Father to Son (1985) ‘How many years must I waste? Today I can’t find nothing nowhere. Tomorrow I might find something somewhere. Give me a future now. I need it so badly now.’

Much of the associated blame and anger was aimed was aimed at Mrs Thatcher, who became hated by many people in a way that no previous Prime Minister had. The Alarm’s Marching On (1984) did not name her but its angry accusations seemed to be aimed at her and it demanded ‘You’d better look at what you have created and think of all the people who hate you’. This may not have been poetic or subtle but it did sum up how many felt.

Yet rock bands like The Alarm were a minority taste. Far more popular in the 1980s were catchy pop songs that were an antidote to rather than comment on hard times. One purveyor of such tunes was Shakin’ Stevens, one of Wales’ most successful modern musicians. Although he came from a deprived Cardiff council estate, his most popular songs were ditties about love, a green door, and Christmas. In this, he was more in tune with popular sentiment than The Alarm and others whose anger was politicized. Indeed, overt faith in the political system was fading and being replaced by apathy and cynicism.

While some turned their backs on party politics, others began to weave a sense of nation into their political views. This was significant because Welshness had largely been a matter of sentiment rather than politics in working-class urban Wales. The changing attitudes were evident in the Welsh iconography of banners at the 1984-5 miners’ strike. One social scientist claimed that Welshness was stepping into a void left by a fragmenting sense of class consciousness.

Theses shifting attitudes to Wales were evident in the output of The Alarm. In 1989, they moved away from their class-based lyrics and released Change, an album inspired by the lead singer’s new found sense of national identity.

Theses shifting attitudes to Wales were evident in the output of The Alarm. In 1989, they moved away from their class-based lyrics and released Change, an album inspired by the lead singer’s new found sense of national identity.

Peters learnt Welsh and a version of the record was also released in that language, making it probably the first fully bilingual album. Change brimmed with a sense of anger and frustration at the state of Wales: ‘I saw a land standing at a crossroads, I saw her wrath in a burned out home, saw her tears, in rivers running cold, her tragedy waiting to explode’ and ‘I see the proud black mountain, beneath an angry sun, under drowning valleys, our disappearing tongue, how many battles must we fight, before we start a war? How many wounds will open before the first blood falls?’

This open sense of Welshness did not help the band’s image outside Wales and their use of a male voice choir on the track New South Wales drew some mirth. Even in Wales, it left the band vulnerable to accusations of clichés. But to me, a teenager at the time, this was all heady stuff and it gave my sense of nationality a distinctly political twist. I surely was not alone.

The Alarm still sounded indistinguishable from so much of western rock music, even with the new lyrics about Wales. Yet that is no reason to dismiss them as part of Welsh culture. Understanding those facets of our culture that are shared with other nations is just as important as appreciating what marks us out as different. Besides, ultimately, there is little in Welsh popular culture that is unique to Wales. When The Alarm sang about the pull of Merseyside, they spoke for the Welsh majority whose cultural inspirations and aspirations did not stop at the border.

Popular music is a powerful social force. It can entertain, inspire and anger. But sometimes it’s nothing more than part of the humdrum of everyday life, something in the background, barely heard or noticed. The Alarm were all this. Yet, whether they were singing about social trends or were just another tune on the radio, the band are a part of the story of modern Wales.

Martin Johnes teaches history at Swansea University and is the author of Wales since 1939.

Sleeper and me

Some thoughts on autobiography and the history of popular music

When I was a student someone bought me Sleeper’s first album for Christmas. I don’t remember who it was or whether I had asked for it. It’s getting frightening how I can’t remember details of my student days. I don’t recall at all where I got Sleeper’s second album from. I have it my head that I borrowed it from someone but never gave it back. But perhaps I imagined that.

Listening to Sleeper now vaguely reminds me of dancing around a room I had in a shared house and of fancying the lead singer, Louise Wener. She embodied the kind of cool girls who smoked, were recklessly romantic and wore jeans and trainers, girls who were out of my league.

Music is a good jogger of the memory. It’s hardly original to point out that hearing a song can remind you of certain people, places and emotions. But when you repeatedly listen to a song or album its associations get confused. I liked Sleeper a lot but their records now prompt a jumbled mix of half-remembered associations that are mixed up with other bands from a period when I spent too much time at indie nights. I can’t even remember for sure whether I ever saw Sleeper live.

I am prompted into self-indulgent nostlagia by having just finished Louise Wener’s autobiography. Its second half, recollections of being a sex symbol in one of Britpop’s key bands, is funny and self-effacing but it’s the first half, the story of being a geeky, music-obsessed teenager in a small town, that makes the book stand out.

Her stories of how music helped her cope with self-doubt, social awkwardness and the ruthlessness of teenagers brought all sorts of things flooding back that I haven’t thought about in a long time. But they also illustrate the power of popular music. Songs are the trigger of memories because they are more than sounds and melodies to have fun to. At its best, music isn’t something in the background of our life events, it’s something that twists and shapes what’s happening in the foreground. It can make us who we are. Wener calls David Bowie ‘the sticking plaster I apply to my teenage awkwardness’. Maybe such power fades as we get older and subsumed by work, family and money, but it’s always there if we want it.

That’s why the history of popular music matters and that’s what historians who write about music should be interested in. Understanding the form, the fashion and the lyrics only makes sense if we look at how they were received. Historians of popular culture should concentrate on the audiences rather than bands.

That’s easier said that done because audiences’ memories of music shift and blur. Some of Wener’s descriptions of seminal moments in her musical life are remarkably detailed and it’s hard not to think that occasionally they are an older, wiser woman looking back on what her younger self probably felt. Indeed, she finishes the book saying she hasn’t made any of it up: ‘It’s all exactly the way I remember it’. Presumably, the implication is that other people might remember it differently.

Events are all about perception. Historians can’t ‘tell it how it was’, because it was always different for different people. The trick is trying to come to generalizations that work, without losing sight of the variations of experience within them.

For some of the groupies in the book, Sleeper were life. For other people, they were just another example of how pretentious Britpop was. For me, they were some great tunes, sang by the kind of unattainable cool woman that I was too nervous to talk to in a dingy Cardiff indie club. Music can be everything and nothing.

British social and cultural history is still lacking a definitive book that looks at the impact of pop music on everyday life. When someone gets round to writing it, Wener’s autobiography will be an excellent source. It might not be typical of the impact of Haircut 100 or David Bowie on every teenager. It might not even be quite right on Wener herself. After all, all autobiography involves reconstructing incomplete memories and some degree of image management, conscious or otherwise. But in this second element, it’s no different to deciding what music you are into. Popular music has never just been about the tunes.

Sleeper on Top of the Pops in 1995, a show that is central to the cultural history of post-war Britain.

Recreation in modern history

[A short essay I wrote for the The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern World (2008)]

Historians have not always treated recreation very seriously as a topic of inquiry but it has always mattered to individuals in the modern world. Work may structure their day but play makes it worthwhile. Whether a song, a film, a game, a drink or even sex, recreation mattered and matters to people. These were not trivial asides; they were integral parts of people’s daily experience and influenced their outlooks on and understandings of the world they lived in. Yet, both the form and meaning of recreation was structured by the wider social and economic contours of life.

Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, modern recreation was shaped by the experience of industrialization. Efficient production demanded that time be organised and segmented. This meant that recreation too became regimented and bound by time, both hindering and enabling play. Long festivals and festivities went into decline with the coming of industry but new opportunities opened up in the time that was designated for recreation, especially on Saturdays, a day which offered escape from work before the more subdued hiatus of the Sabbath. Furthermore, modern industrial conditions brought rising incomes for the working and middle classes, enabling people to purchase pleasure in their spare time. By the late nineteenth century, people in industrial countries were spending money on tobacco, alcohol, gambling, sport, confectionary, and even holidays.

Of course, the boundaries between work and recreation were never impermeable. People talked, joked and even played while at work, and outside work domestic, family and religious chores and duties could lack the fun that should characterize play. Furthermore, as leisure itself was commercialized to take advantage of the rising demand, one person’s recreation became another’s employment. Similarly, developments like bicycling, which gained huge popularity at the very end of nineteenth century, served as both a means of travel for work and pleasure.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, industrialization may have changed the patterns of play in those communities that underwent it, but there was much continuity in its forms. The pleasures of drink and the escapism of drunkenness were as popular after the industrial revolution as they were before it. Music, dancing and sports were also integral parts of popular culture in both the premodern and the modern worlds. But modernization was bringing rationalization and organization, and it increasingly became the norm for such older collective but informal recreational traditions to be organized into clubs and societies. Competitions and rules became more formalized and the pursuit of pleasure justified by arguments for its moral and physical worth. Nowhere was this is clearer than in the world of sport, where, led by the British and to a lesser extent the French, new rules, competitions, and traditions were established from the late nineteenth century. Sports became part of the building of the character and physique of young men, a tool to ensure national survival in the midst of international tensions and ideas of social Darwinism. The economic and political patterns of a world of empires also took sports across the globe, introducing them to non-industrial territories likeIndia, where they quickly gained a local following, although not always in the spirit or form that their imperial masters had intended.

The rationalization of play was important as recreation increasingly became a contested political and moral space in the industrializing world. Drink had long since attracted religious oppositions but as religion itself was undermined by the spread of education, science and recreation, churches turned their attention to other pastimes that were thought to distract hearts and minds from God. In Catholic countries in particular the influence of the church was strong and this hindered the development of some modern forms of recreation such as formalized gambling. Recreation was also under attack from the growth of rational and scientific thinking that thought time and effort should only be employed on matters that were beneficial to the mind, body and community. Thus while the arts were widely deemed rational recreation, more populist pleasures were not, particularly when there were undertones of violence or debauchery. This was evident in the gradual growth in distaste for pastimes that involved cruelty to animals. However, precise attitudes towards what was socially acceptable obviously varied across cultures, as can be seen in the survival of the bullfight as a popular form of entertainment in Spain nearly two centuries after similar pastimes were outlawed in Britain.

The twentieth century

By the twentieth century technological developments were broadening the range and possibilities of recreation. The most significant invention in the field of recreation was the cinema, an international medium that literally changed the way people saw the world. In the early twentieth century, it opened up horizons and imaginations and had a profound effect on people individually and collectively; lives became less drab, wars and threats overseas seemed more real. It also began the trend of the Americanization of global popular culture and created global stars like Charlie Chaplin. The best films was not all American as, say, the great silent pictures of Weimar Germany or the sound films of 1930s France showed, but, as technologies got bigger and more expensive, it was increasingly difficult for other nations to produce films of the scale, spectacle and sheer impact of Hollywood.

Sport was another global phenomenon. Soccer, in particular, became an obsession that transcended national boundaries, although it was often utilized as a symbol of national and political pride, not least by the totalitarian regimes of left and right. The Olympic Games too became associated with deliberate and incidental exhibitions of national status, despite its initial conception as a celebration of international togetherness. Nonetheless, events like the World Cup and the Olympics did become genuine shared experiences that stretched across the globe.

Of course, not all recreation was communal. The home remained an important site of recreation, especially for women. Reading, embroidery, pets and even sex were things that could be enjoyed in the home of the growing literate masses. The development of the radio after the First World War was especially important in encouraging domestic recreation, although the relative expense of a set meant that it was not until the Second World War, fed by a hunger for news, that it achieved a truly mass audience inEurope. After the 1939-45 conflict, aided by the new rising prosperity, television became the dominant and ubiquitous source of both recreation and information. By the late 1960s it was the norm for homes in Europe, North America andAustralasiato have a set. It was simultaneously a private and shared experience: millions of people watched the same programmes but they did so from the comfort of their own homes. The development of satellite broadcasting in the 1960s enabled the live audiences for significant sporting and news events to extend around the globe, while the content of other programming, both educational and trivial, was a mix of the local and the imported.

For all its far-reaching significance in the west, television remained beyond the reach of those in poverty in the developing world. The reach of the globalized popular culture that was at the heart of recreation in the second half of the twentieth century was still limited by the realities of inequalities of wealth. Indeed, even within the west, a lack of access to popular recreation compounded the more fundamental miseries of poverty: poor diet and housing. It is the poorest’s lack of access to modern forms of recreation that undermines Marxist views of leisure as an opiate of the masses, something to distract them from wider political and economic struggles. This is not to suggest that that movies, drugs, alcohol or sport could not have this function but limited access certainly limits recreation’s political influence.

Nor was it just money that constrained modern recreation. Leisure was often highly gendered, reinforcing and reproducing wider female subordinate roles, from simply seeing recreation as the prerogative of only the male wage earner to employing women in brothels as entertainment for men. Racial prejudices too could, officially and unofficially, prevent people from partaking in everything from public dances to world title boxing bouts. Such restrictions eased as the west gradually became more racially tolerant after the Second World War and leisure even became an arena that encouraged such developments. Popular music was key here. Although black musical forms like jazz and the blues were initially widely distrusted because of their racial base, they gradually crossed over into mainstream popular culture, entertaining and influencing white people across the western world. Rock’n’roll in the 1950s and pop in the 1960s were dominated by both white artists and audiences but their roots lay in black musical forms.

Popular music in this era started as part of a new youth culture but, as generations aged, it became part of mainstream recreation. Like much modern recreation, it became a huge global industry in its own right and, even when associated with social and political rebellion, popular music was intensely commercialized. It also encapsulated the nature of global popular culture: strong common threads, structures and forms that absorbed local influences and then transmitted them across national boundaries, a process engendered and driven by the globalized economy and mass media. Recreation was thus not only an integral part of people’s lives across the globe, it was also an arena that made a global culture something more real than simply the abstract flows of economic and political ties.

Further reading

Briggs, Asa and Burke, Peter, A Social History of the Media: From Gutenberg to the Internet, Cambrige: Polity, 2005. Seminal introduction to a key form of recreation.

Clarke, John and Critcher, Chas, The Devil Makes Work: Leisure in Capitalist Britain,London: Macmillan, 1985. A loosely-Marxist interpretation of leisure history, with implications beyond itsUK casestudy.

Critcher, Chas, Bramham, Peter and Tomlinson, Alan, eds., Sociology of Leisure: a Reader.London: E & F N Spon, 1995. Useful introduction to sociological interpretation of contemporary recreation.

Guttmann, Allen, From Ritual to Record: The Nature of Modern Sports,ColumbiaUniversity Press, 2004. A seminal, wide-reaching although US-centred study of the development of modern sport, employing modernization theory.

Pierre Lanfranchi, Christine Eisenberg, Tony Mason & Alfred Wahl, 100 Years of Football: The FIFA Centennial Book (London, 2004). A global account of the global game.

Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey, ed. The Oxford History of World Cinema.OxfordUniversity Press, 1999. A hefty and wide ranging study of film.