First published in D. Levinsen and K. Christensen (eds.), Encyclopaedia of World Sport, Great Barrington, USA: Berkshire Publishing, 2005.

The United Kingdom was the birthplace of modern sport. From the drawing up of rules to the development of sporting philosophies, Britons have played a major role in shaping sport as the world knows it today. This role meant that British sport was overly insular and confident in its early days, while its post-1945 history was marked by doubts and crises as the nation realised that the rest of world had moved on, a situation that mirrored the UK’s wider crisis of confidence in a post-imperial world.

Pre-industrial sports

Pre-industrial sport in Britain resembled those in much of Europe. It was not a clearly demarcated activity but rather part of a communal festive culture that saw people congregate to celebrate high days and eat, drink, gamble and play. The sports of the people reflected their lives: they were rough, proud and highly localized. Rules were unwritten and based on customs and informal agreements that varied from place to place according to local oral traditions. ‘Folk’ football was one of the most common and popular examples of sport. It had existed in different forms across England and Wales since at least medieval times, but it resembled a mêlée more than its modern descendant. Traditional boundaries within rural society were celebrated within such games, with contests between parishes, young and old and married and unmarried. Other sports played at communal festivals included running races and traditional feats of strength such as lifting or throwing rocks.

The physicality of pre- and early-industrial Britain was also reflected and celebrated in bareknuckle prize fighting, although this widespread sport could not always be clearly distinguished from public drunken brawls. The brutality of life was further evident in the popularity of animal sports. Bull baiting and cock fighting were amongst the most popular but such recreations increasingly came under attack in the middle of the nineteenth century from middle-class moralists. The foxhunting of the upper class was not attacked, suggesting that the crusades owed something to concerns about the turbulent behaviour of the workers rather than just the suffering of animals.

The attacks on animal sports were part of a wider process of modernization that saw Britain transformed into the industrial workshop of the world. Urbanization, railways, factories, mills and mines saw Britain transformed, economically, environmentally and psychologically. Modern sport was forged within this heady mix of breakneck change; new ways of working and living brought new ways of playing. As well as the assaults on animal sports, folk football was attacked in towns because it disrupted trade and the general orderliness of the increasingly regimented world that industry was creating. Bareknuckle fighting too was attacked as a threatening symbol of a violent working class that unsettled an establishment already worried by the rise of political demands from the workers.

There was, of course, much continuity between the worlds of pre-industrial sport and the commercialised and codified games that emerged towards the end of the late nineteenth century. Cock fighting and prizefighting, for example, survived the attempts to outlaw them, but left the centres of towns for quiet rural spots or pubs and back streets that were away from the surveillance of middle-class authorities. ‘Folk’ football too lived on, although apparently on a smaller scale that was less orientated around traditional holidays and community celebrations. Its survival in this form surely underpinned the speed with which the codified form that emerged from the public schools was taken up by the masses across Britain.

The emergence of modern sport

Whilst forms of football were on the decline in mid-nineteenth century Britain, they were actually being adopted in the country’s public schools, as a means of controlling the boys and building their character, both as individual leaders and socially-useful team players. Underpinning the values that football was thought to cultivate were ideas of masculinity and religious conviction. Muscular Christianity deemed that men should be chivalrous and champions of the weak but also physically strong and robust. The belief that such qualities would create the right sort of men to lead the British Empire meant that a cult of athleticism, whose importance ran far deeper than mere play, developed within the English public schools.

Such traditions found a natural extension in the universities. It was here, particularly at Cambridge, that much of the impetus for common sets of rules developed in order to allow boys from different public schools to play together. It was from such beginnings that the moves towards codification of rules and the establishment of governing bodies mostly sprang. Most famously, representatives of leading London football clubs, including former public schoolboys, met in London in 1863 to establish a common code of rules for football and form the Football Association to govern the game.

With rules and a governing body behind them, former public schoolboys went out into the world, taking their games with them. Not only did this encourage the diffusion of sport outside British shores but it also led to modern sport being taken to the masses by a paternal elite who partly sought to better the health and morals of the masses, not least because of fears of national decline. Games like soccer and rugby were well-suited to urban, industrial communities, requiring only limited time and space and they very quickly developed in popularity amongst the working classes across Britain during the late nineteenth century. Such developments created an apparent homogenization of sports culture across Britain but there were distinct local variations. Knurr-and-spell and hurling, for example, enjoyed some popularity in the north of England and Scottish highlands respectively. Such traditional games furthered the continuity between pre-industrial and industrial sport but even they had to develop modern organisations and sets of rules to survive.

Modern British sport was not entirely rooted in the public schools and their spheres of influence. In Sheffield, for example, there were independent attempts to draw up sets of rules for football. Even amongst the southern middle classes, there developed popular sports, such as tennis, whose origins lay elsewhere. Golf could trace its written rules back into the eighteenth century Scotland but it was not until the wider sporting revolution and mania of the late nineteenth century that the sport’s popularity exploded amongst the British middle classes. Cricket was another sport whose written rules were drawn up in the eighteenth century and thus predate the public-school cult of athleticism.

Professionalism in cricket also dated back to the eighteenth century but as the phenomenon developed in other sports in the late nineteenth century, it, like other sports, developed an obsession with amateurism that was closely allied to the public-school ethos of fair play and playing for the sake of the game. Above all, amateurism was about projecting social position in a period of social change and mobility. To be an amateur in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain was to not need to be paid to play. Thus in cricket, where amateurs and professionals often played in the same team, social distinction was preserved through the use of different changing rooms, different ways of writing names and initially requiring professionals to labour with bowling and even menial tasks such as cleaning the kit. Yet, despite the snobbery that underpinned amateurism there was a general reluctance in most sports to impose explicit class-based restrictions on participation, though the Amateur Rowing Association was a notable exception. Furthermore, the reality of amateurism did not always match the rhetoric. Nowhere was this clearer than in the case of cricketer W. G. Grace (1848-1915). Undoubtedly the most famous sportsman of the Victorian era, Grace was a doctor and a gentleman but he was also supremely competitive and certainly not above gamesmanship and demanding excessively generous expenses.

It was in rugby and soccer that the issue of professionalism became most controversial. The growth of socially-mixed northern teams led to broken-time payments, where working men were compensated for missing work in order to play. Such payments however not only offended the amateurist principles of some of the elite, but they also threatened to take power away from the middle classes, both on and off the playing field. In soccer, professionalism was sanctioned in 1885 in order to ensure the middle-class Football Association retained control of the game, but it was soon tempered with severe controls on players’ freedom to move clubs and be paid what a free market might allow. Such tensions, fuelled by north-south rivalries, led rugby to split into two codes (which later became known as league and union) in 1895. Rugby league became a sport whose whole existence and identity was closely interwoven with ideas of working-class identity in northern England.

Watching and playing

Clubs could afford to pay players because soccer and rugby had become something that people watched as well as played. This owed much to the establishment of cup competitions, which, fed by civic and regional rivalries, gave some purpose and excitement to matches. In the industrial north of England, the growing crowds began to be charged for the privilege of watching and hosted in purpose-built grounds. Such crowds worried the class prejudices of social onlookers, who complained about the drinking, gambling and partisanship of supporters, as well as the impact on the nation’s health of a population that spent its free time watching rather than playing.

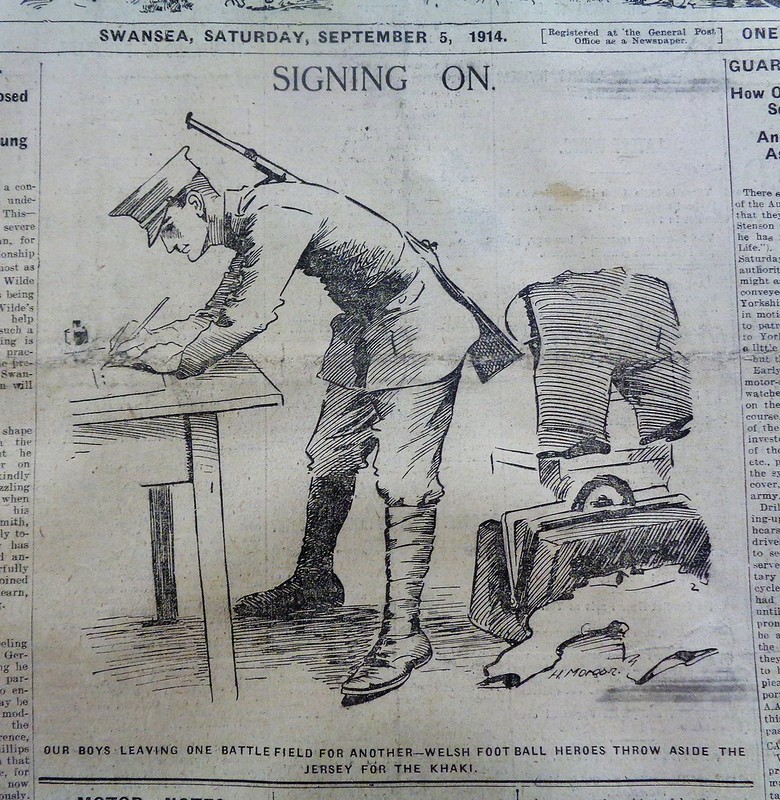

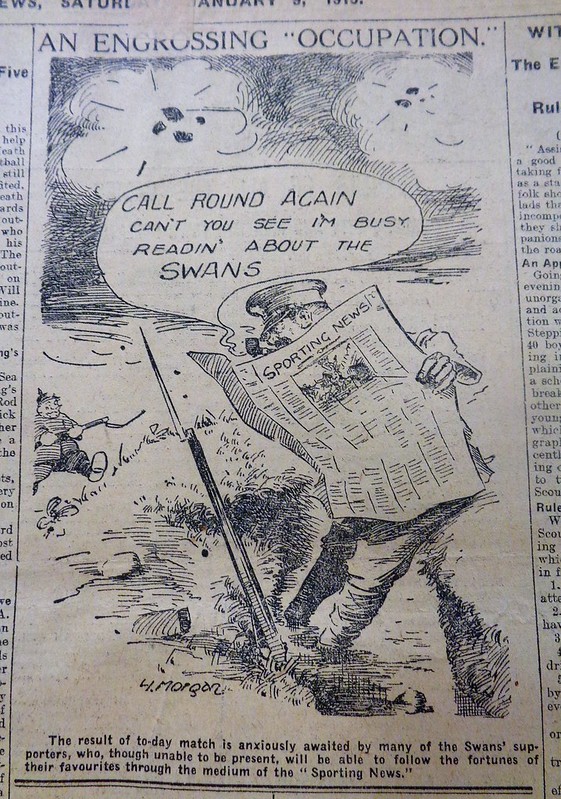

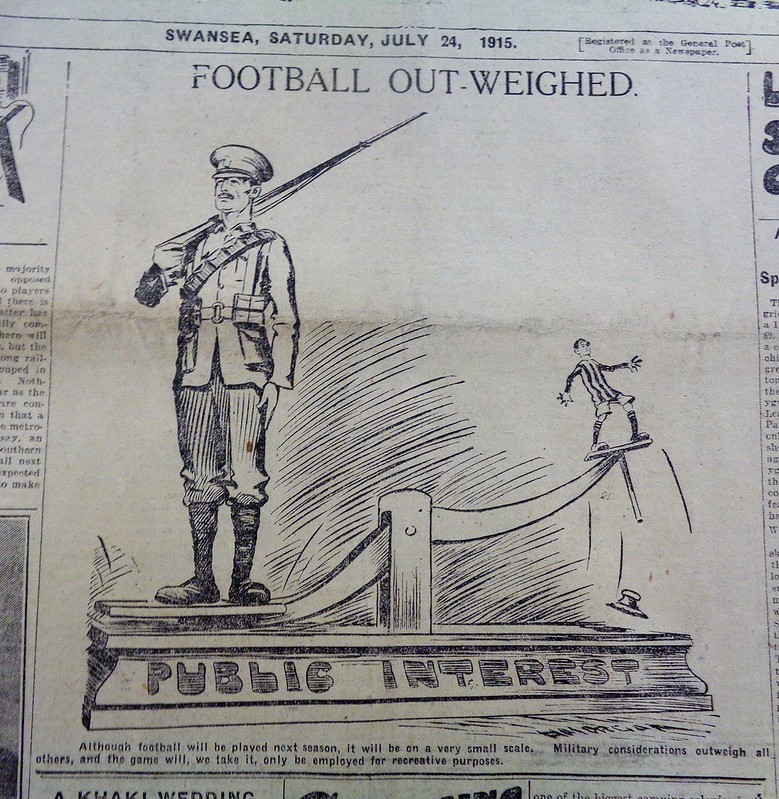

When soccer played on after the outbreak of war in 1914 the reputation of professional sport plummeted amongst the middle classes. Nonetheless, sport was to play an important role in maintaining troop morale at the front. In the aftermath of the Great War spectator sport reached new heights of popularity. The largest league games in soccer could attract as many as 60,000; yet, beyond drinking and gambling, disorder was rare. This led the sport to be celebrated as a symbol of the general orderliness and good nature of the British working class at a time of political and social unrest at home and abroad.

For spectators professional sport offered an exciting communal experience, where the spheres of home and work could be forgotten in the company of one’s peers. As such, crowds at professional soccer and rugby league became overwhelmingly masculine enclaves that fed a shared sense of community, and perhaps even class, identities. Sport’s ability to promote civic identity was underpinned not by the players, who being professional were transient, but by the supporters and the club sharing the name of its town or city.

Yet these crowds were not actually representative of such civic communities. Professional sport was mostly watched by male skilled workers, with only a sprinkling of women and the middle classes. The unemployed and unskilled workers were, by and large, excluded by their own poverty and the relative expense of entry prices. Consequently, as unemployment rocketed in parts of Britain during the inter-war depression, professional sport suffered; some clubs in the hardest hit industrial regions actually went bankrupt. Working-class women meanwhile were excluded from professional sport by the constraints of both time and money. Even the skilled workers did not show an uncritical loyalty to their local teams. Professional sport was ultimately entertainment and people exercised judgement over what was worth spending their limited wages on seeing.

Men played as well as watched and the towns of Britain boasted a plethora of different sports, from waterpolo in the public baths, to pigeon races from allotments, and quoits in fields behind pubs. Darts, dominoes and billiards flourished inside pubs and clubs. Space was, of course, a key requirement of sport but it was at a premium and the land that was available was heavily used. For all the excitement that sport enabled men and women to add to their lives, they were still constrained by the wider structures of economic power.

Working-class sport could not be divorced from the character of working-class culture. Local sport was thus intensely competitive and often very physical. In both football codes, bodies and fists were hurled through the mud, cinders and sawdust of the rough pitches that were built on parks, farmland and even mountainsides. But, win or lose, for many men and boys, playing sport was a source of considerable physical and emotional reward. For many youths, giving and taking such knocks was part of a wider process of socialization: playing sport was an experience that helped teach them what it meant to be a man. Similarly, working-class sporting heroes reflected the values and interests of the audience; they were tough, skilled and attached to their working-class roots.

Cricket was the national sport of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century England, in that its following was not limited to one class or region. Matches in urban working-class districts may have lacked the pressed white flannels or neat green wickets of a test match at Lord’s but they shared the same intricacy and subtlety of play. The contest between the skill and speed of the bowler and the technique and bravery of the batsmen was one familiar to both working-class boys and upper-class gentlemen. Cricket’s popularity owed something to the rural image of England that it encapsulated. Cricket on the village green was an evocative and emotive image, employed even by a prime minister at the end of the twentieth century. Yet, from the English elite, cricket spread not only to the masses of the cities but also the four corners of the vast British Empire, where it enabled the colonies to both celebrate imperial links with the motherland and also take considerable pride in putting the English in their place.

Like cricket, horseracing had been organised since the eighteenth century and was followed by all classes from Lords to commoners. Gambling was at the core of its attraction and a flutter on the horses was extremely popular, despite its illegality (until 1963) when the bet was placed in cash and outside the racecourse. As with soccer, the sporting press offered form guides and was studied closely, with elaborate schemes being developed to predict a winner. The racecourse itself was often rather disreputable, with the sporting entertainment on offer to its large crowds being supplemented by beer, sideshows and, in the nineteenth century, prostitutes. It provided the middle classes with an opportunity to (mis)behave in a manner that would be impossible in wider respectable society.

Respectability did matter on the golf course and in the clubhouse. Although it had something of a working-class following, especially in Scotland, golf was a sport of the middle class and its clubs were important social and business networks that conferred privilege and status within the local community upon their mostly male membership. Tennis too had both a middle-class profile and a social importance that often marginalized actually playing the game. Like archery and croquet before it, for the urban middle class of the early twentieth century, the tennis club was an opportunity to meet and flirt with members of the opposite sex of the ‘right sort’. In such ways, sport became an important part of the lives of a middle class that was increasingly otherwise socially isolated in the new suburbs.

As in the rest of Europe, the shadow of war was hanging over the suburbs by the 1930s. In such an atmosphere, sport itself became to be increasingly political. The England soccer team were even told by the appeasing Foreign Office to give the Nazi salute when playing an international in Berlin in 1938. The threat from Germany also led to renewed investment in playing fields, as concerns resurfaced about the fitness of a nation on the brink of war. Unlike in the First World War, sport was fully promoted during the 1939-45 conflict, as an improver of spirits and bodies for civilians and troops alike.

Britain finished the Second World War victorious but physically and economically exhausted. In the austerity that marked the late 1940s, sport was one readily obtainable relief and, encouraged by growing radio coverage, soccer, rugby, cricket and boxing enjoyed huge crowds. There were also large crowds at the 1948 Olympics, which London stepped in to host with the hope that the games would rejuvenate tourism and help put some colour into the post-war austerity. The games were an organisational success and even made a profit, the last Olympics to do so until 1984. After leaning towards isolationalism in both politics and sport during the inter-war years, the post-war period saw a new awareness in Britain of its relationship with the rest of the world. With the Empire being dissolved, international competitions like the Olympics began to matter more as indicators of national vitality. The conquest of Everest in 1953 offered some optimism and confidence for the future but soccer, Britain and the world’s most popular game, was not reassuring for its inventors. England’s first forays into the World Cup were far from successful and indicated that the country’s loss of global power was not confined to the political sphere.

The television era

As economic prosperity returned in the 1950s, spectator sport suffered a downturn in popularity, as it competed against the lure of shopping, cars and increased domestic comforts, of which television was one of the most alluring. Such alternatives were particularly appealing to older men and thus the 1960s seemed to witness crowds, in soccer at least, become younger. One consequence was the rise of a youthful football fan culture that utilised humorous but obscene and aggressive chants and promoted fighting between rival supporters. The media spotlight, increasingly looking for sensational stories from across sport, amplified the hooligan problem but from the late 1960s to 1980s it was a genuine and widespread subculture that drew more upon the thrill of limited violence than any sense of a disempowered youth rebelling against the world.

Initially, there was only limited sport shown on television and many sporting authorities, not least soccer, feared that coverage would kill live audiences. Yet others, like golf and horseracing, saw television as an opportunity to develop their popularity and thus courted its coverage. The growth of televised sport was therefore sporadic; in the 1950s and 60s it was too often limited to edited highlights or live coverage of only the biggest events in the sporting calendar.

Yet televised sport was to become hugely popular and influential. In the 1960s, coverage of the Olympics and the 1966 World Cup won mass audiences and turned the events into shared celebrations of a global sporting culture. Wimbledon became, for most people, a television event rather than a live tennis championship, while rugby league became inextricably linked to the northern tones of commentator Eddie Waring. By the 1970s, television coverage had also helped turn rugby union’s Five Nations Championship into a very popular competition that transcended the sport’s middle-class English foundations.

Television also opened up the opportunities to commercially utilise sport, not least through sponsorship. Athletics was one sport where television and sponsorship increased its profile and popularity, but this also created tensions between the amateurist traditions of the administrators and the commercial demands of the stars. Other sports suffered similar tensions and responded by either slowly becoming explicitly commercial, as in the case of professional golf, or turning a blind eye to transgressions of the amateur code as in the case in athletics and parts of rugby union. Yet, ultimately, money talked and amateurism gave way to commercial pressures across senior sport.

The changes television was starting to bring about could be radical. Cricket proved surprisingly willing to embrace change and even introduced a one-day Sunday League as early as 1967, as it searched for a more accessible and exciting one-day format to supplement the waning four-day county game. After the invention of colour television, snooker was televised from the late 1960s and the sport was transformed from the realm of smoky pubs to something resembling a national craze. The relatively static nature of the game meant that it was cheap to broadcast and conducive to dramatic close ups. Snooker also had the characters and personalities that the media was increasing seeking in its coverage of sport.

The real commercial boost from television came in the 1990s, with the development of satellite television. Soccer was seen as the key to securing an audience for the new medium. Rupert’s Murdoch’s Sky thus spent enormous sums on securing and then keeping the rights to televise the game’s senior division. After the 1980s – when hooliganism and the fatal horrors of disasters at Bradford, Heysel and Hillsborough had seen English football sink to its lowest ebbs of popularity and standing – Sky’s millions enabled the game’s upper echelons to reinvent itself in the 1990s. New all-seater stadia (enforced by the government to avoid a repeat of the 96 deaths at Hillsborough in 1989) made watching soccer both safer and more sanitised, an influx of talented foreign players raised standards of play, while a more cynical and overtly commercial edge developed amongst the game’s owners and administrators. Players were the main beneficiaries as their profile, wages and sponsorship opportunities rapidly escalated in the now hugely fashionable and celebrity-conscious game. David Beckham epitomised this transition, with his pop-star wife, countless sponsorship deals and media-frenzied private life. Fans meanwhile could watch more soccer than ever on television but actually attending matches was becoming extortionately expensive. Other sports were keen to follow soccer’s example. Rugby league became Super League, its teams gained American-style epithets and the sport even moved from winter to the less crowded television schedules of summer. Rugby union, fearing being left behind, suddenly abandoned its strongly amateur heritage and turned professional in 1995, a move that was to bring it as many financial headaches as rewards.

Identities and inequalities

In the second half of the twentieth century, spectator sport and television may have become interwoven in a relationship built on money, but participatory sport did not die out, although it too became part of a leisure industry that sold everything from training shoes to personal gyms. As throughout the twentieth century, participation remained skewed by class. The wealthier appeared not only more able to afford to play sport but they also appeared more interested in doing so. The foundations and boundaries of the British class system were becoming increasingly blurred and the diminishing class associations of the most popular sports reflected that. Yet historical legacies and financial requirements still meant that equestrian sport remained beyond the reach and often tastes of the masses, whilst activities such as boxing and darts remained closely allied to working-class culture. Success at such sports could take performers out of their working-class origins but this did not end the cultural resonances of the sports that had been built up over a century.

Nor were the gender biases of sport ended by the equal opportunities ethos of the late twentieth century. Playing and watching sport remained far more popular amongst men, despite the significant advances made in female participation rates and the profile of some leading sportswomen. Olympic athletes like Denise Lewis or Kelly Holmes may have ventured into the celebrity world of sports stardom but, at the start of the twenty-first century, women are still on the margins of sport, in terms of numbers, profile and culture.

Athletes from Britain’s ethnic minorities have, however, broken through into the mainstream of nearly all the country’s most popular sports. In the early twentieth century, there had been occasional black athletes in boxing and soccer in particular, but it was the 1970s that saw British sport become genuinely ethnically-mixed, when the sons of the first generation of large-scale immigration reached adulthood. By the twenty-first century, England’s national teams had even had black and Asian captains in soccer and cricket respectively. Such achievements were not simply symbolic but also encouraged a degree of wider racial integration in national culture. Yet sport has also been, and continues to be, the site of explicit racism (notably in the form of soccer chants) and more subtle preconceptions about the playing abilities of different ethnic groups. Such prejudices partly explain why few professional soccer players have emerged from the UK’s large Asian population.

While little sustained media attention was ever devoted to sporting inequalities based on class, gender or ethnicity, nationhood was a topic of widespread popular interest. When in 1999 Chelsea Football Club fielded a team that did not include a single British player, there were debates about globalization’s potential impact on the future success of British international sides. Sport had always played an important role in shaping national identity within the United Kingdom. For the Welsh, Scottish and Irish, it had an important symbolic role in affirming their nationhood and equality with England. While the Scots and Welsh enjoyed cutting the English down to size at football and rugby, the Irish increasingly rejected these sports in favour of their own indigenous games, such as Gaelic football and hurling, which could be used to symbolise a separate, and non-British, cultural heritage.