In 1907, the first step towards the devolution of education was taken with the creation of a Welsh Board of Education to oversee schools funded by the state. Its head was Owen M. Edwards, a history professor who had endured the Welsh Not in his own education. He was determined that schools should meet the needs of the Welsh nation and recognised that a knowledge of a nation’s history could inspire confidence and patriotism in its people. One of the Board’s first steps was to issue a new regulation that the history of Wales should be taught in every school.

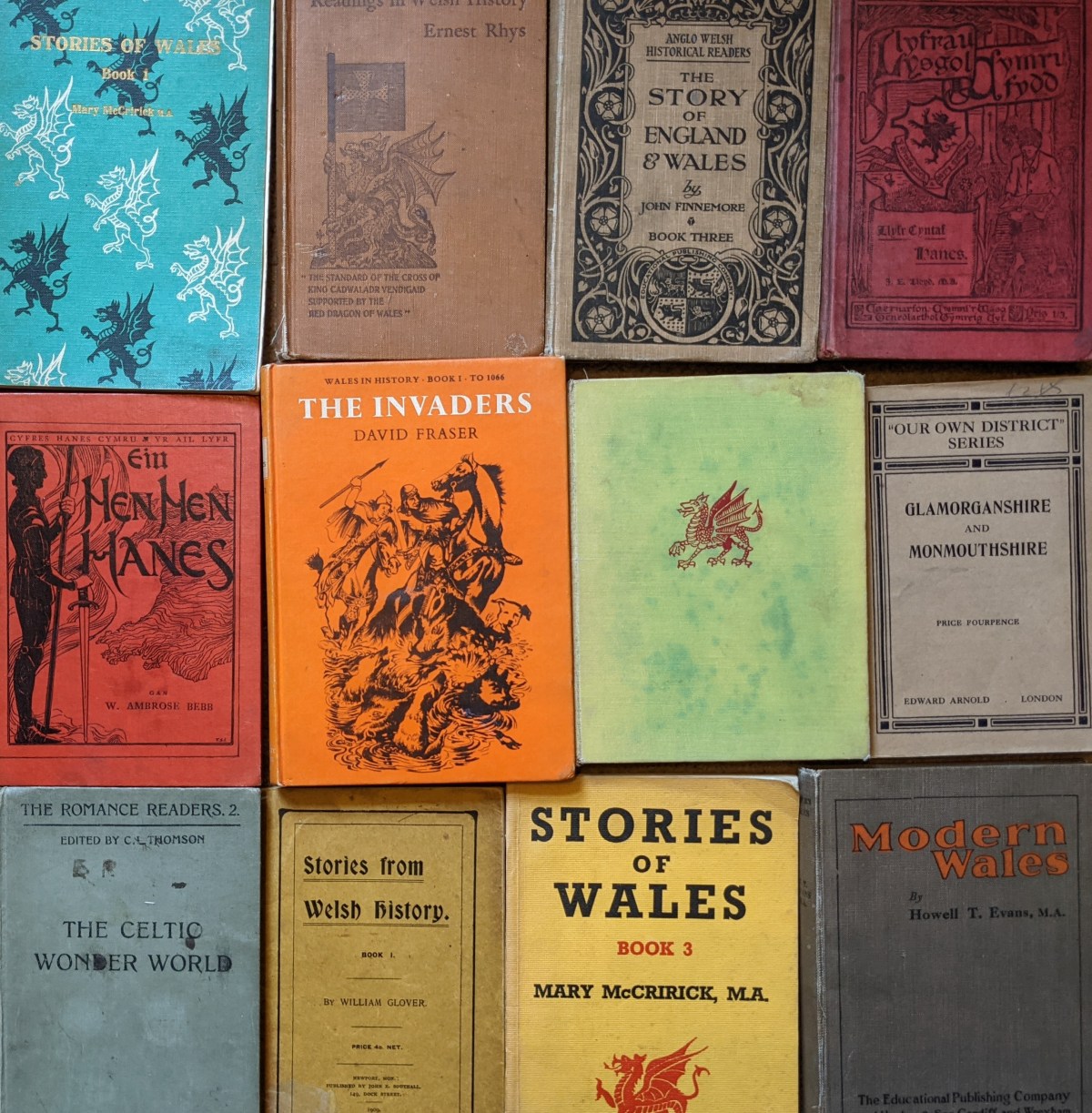

In the absence of any kind of national curriculum, the state actually had little direct control over what happened in classrooms and which specific topics subjects like history focussed on. The new directive on Welsh history was not widely taken up and Wales remained a peripheral or non-existent part of most children’s history education, marginalised in favour of stories of English Kings and Queens. This was partly rooted in what teachers felt they knew and their sense of what history should be, but another problem was a lack of suitable Welsh history textbooks. Consequently, a series of textbooks were published to support the teaching of Welsh history but these were not widely adopted.

More than a century later, the situation remains similar. The creation of a National Curriculum in the late 1980s did tighten curricular instructions to require rather than recommend the history of Wales to be taught. The National Curriculum also gave some direction on which topics Welsh History should entail but this specificity has been lost with the new Curriculum for Wales. This requires that all schools teach the history of Wales until GCSE but it has no requirements over what that should entail or what proportion of history teaching should focus on Wales. Instead there is a general statement that pupils should receive ‘consistent exposure to the story of their locality and the story of Wales’. But what this means in practice is left in the hands of individual schools and teachers.

The precise results of this are not entirely clear. Welsh Government does not collect data about what topics are taught within schools and thus does not know what its requirement for the teaching of Welsh history is leading to in practice. It did commission a small-scale report from Estyn, published in 2021. Estyn found that in primary schools there was some enthusiasm for teaching local history, but in a few schools there was no Welsh history taught at all. In secondary schools, the picture was worse. Estyn concluded, ‘In many secondary schools, lessons include only cursory references to local and Welsh history. Teachers do not plan opportunities for pupils to develop a coherent knowledge and understanding of the local area and Wales across periods’. Most pupils thus seem to leave school with some knowledge of their local area and a few events in Welsh history, but little sense of how these things connect or the overall history of Wales, as both a nation in its own right and as part of the United Kingdom.

Like more than century ago, there is an assumption that part of the problem is resources and the government is investing in the creation of new Welsh history materials for schools. But no matter how good these are, there is no guarantee they will be used. Teachers often prefer to stick to topics they know and understand and to resources that experience has shown work in the classroom. The provision of Welsh history is caught in a vicious circle where teachers do not learn much about it in their own education and then do not feel equipped to teach it in their own careers.

There is, I believe, a genuine desire in Welsh Government to see more Welsh history taught. Online claims that a unionist Labour government is denying Welsh children knowledge of their national past to stop them becoming nationalists are far fetched. But Welsh Government is wedded to one of the central principles of its Curriculum for Wales – that schools should not be told what knowledge they should teach. If schools have the freedom to choose what subject matter they teach, they have the freedom to continue with what they are already doing, no matter what a government wants to happen. The result of this is that in schools the teaching of Welsh history remains bitty and inconsistent.

Labour and Plaid Cymru have repeatedly stated their commitment to ensuring that Welsh history is taught in our schools. If they are serious about wanting that to happen in a meaningful and consistent way, then a significant change of policy is needed. Commissioning more resources is not going to achieve any significant transformation. Nor will strengthening guidance. Instead, what is required is specific compulsion.

This does not need to extend too far. It does not need a complete overhaul of the Curriculum for Wales or an abandonment of all its principles. The government could simply mandate a compulsory ‘Wales’ course to be taken under the Humanities Area of Learning in Year 8. The course could offer pupils an overview of the key events in the history of Wales. These would not need to be events unique to Wales. Teaching Wales’s roles in the slave trade and the world wars, for example, matters too. There could be accompanying material and activities tailored to the different regions of Wales to ensure the commitment to local history is not lost. It could also look at key poems and novels in both our languages.

Most importantly, the course could go right up to the present day and include coverage of how the Senedd works, the state of Wales and Welsh society today. That would ensure the Curriculum’s aspirations to teach Welsh citizenship and political knowledge are actually delivered.

Some will fear that such a venture is too political. But education is political. Deciding to teach any topic is a political question. The Welsh language is taught to all children because there is a broad political consensus that this is a good thing. It is difficult to imagine any serious opposition to the idea that Welsh history should be taught properly. Any opposition to a mandatory Wales course is likely to come from fears over how it will be taught and what might be derived from that. But history does not offer any simple lessons for today and can be read in different ways. If the material is designed correctly, it will make the children ask questions about the nature of Wales as much as it will give them answers.

The authorities have required the teaching of the history of Wales for more than 100 years. That has not delivered any consistency for pupils. There are schools that teach a lot of Welsh history and others that teach very little. For individual pupils this matters less than questions around literacy and numeracy, but if we are serious about preserving Welsh identity and Welsh culture and wanting people to engage with our young democracy, we need people to understand that Wales matters. They do not need to agree why or how, but discussion should come from a basis of shared knowledge.

The Curriculum for Wales does not deliver that and no amount of new Welsh history resources are going to change that. If Welsh Government is serious about its commitment to Welsh history, it needs to abandon its commitment for a completely open curriculum. It needs to move towards the idea that, even just for one year in one subject, there is some specific knowledge that every pupil should learn.

Martin Johnes is professor of Welsh history at Swansea University.