A short video I made for a Welsh Government event about history in the Curriculum for Wales.

Tag: education

The Curriculum for Wales, Welsh History and Citizenship, and the Threat of Embedding Inequality

Welsh education is heading towards its biggest shake up for two generations. The new Curriculum for Wales is intended to place responsibility for what pupils are taught with their teachers. It does not specify any required content but instead sets out ‘the essence of learning’ that should underpin the topics taught and learning activities employed. At secondary school, many traditional subjects will be merged into new broad areas of learning. The curriculum is intended to produce ‘ambitious and capable learners’ who are ‘enterprising and creative’, ‘ethical and informed citizens’, and ‘healthy and confident’.

Given how radical this change potentially is, there has been very little public debate about it. This is partly rooted in how abstract and difficult to understand the curriculum documentation is. It is dominated by technical language and abstract ideas and there is very little concrete to debate. There also seems to be a belief that in science and maths very little will change because of how those subjects are based on unavoidable core knowledges. Instead, most of the public discussion that has occurred has centred on the position of Welsh history.

The focus on history is rooted in how obsessed much of the Welsh public sphere (including myself) is by questions of identity. History is central to why Wales is a nation and thus has long been promoted by those seeking is develop a Welsh sense of nationhood. Concerns that children are not taught enough Welsh history are longstanding and date back to at least the 1880s. The debates around the teaching of Welsh history are also inherently political. Those who believe in independence often feel their political cause is hamstrung by people being unaware of their own history.

The new curriculum is consciously intended to be ‘Welsh’ in outlook and it requires the Welsh context to be central to whatever subject matter is delivered. This matters most in the Humanities where the Welsh context is intended to be delivered through activities and topics that join together the local, national and global. The intention is that this will instil in them ‘passion and pride in themselves, their communities and their country’. This quote comes from a guidance document for schools and might alarm those who fear a government attempt at Welsh nation building. Other documents are less celebratory but still clearly Welsh in outlook. Thus the goal stated in the main documentation is that learners should ‘develop a strong sense of their own identity and well-being’, ‘an understanding of others’ identities and make connections with people, places and histories elsewhere in Wales and across the world.’

A nearby slate quarry could thus be used to teach about local Welsh-speaking culture, the Welsh and British industrial revolution, and the connections between the profits of the slave trade and the historical local economy. This could bring in not just history, but literature, art, geography and economics too. There is real potential for exciting programmes of study that break down subject boundaries and engage pupils with where they live and make them think and understand their community’s connections with Wales and the wider world.

This is all sensible but there remains a vagueness around the underlying concepts. The Humanities section of the curriculum speaks of the need for ‘consistent exposure to the story of learners’ locality and the story of Wales’. Schools are asked to ‘Explore Welsh businesses, cultures, history, geography, politics, religions and societies’. But this leaves considerable freedom over the balance of focus and what exactly ‘consistent exposure’ means in practice. If schools want to minimize the Welsh angle in favour of the British or the global, they will be able to do so as long as the Welsh context is there. It is not difficult to imagine some schools treating ‘the story of Wales’ as a secondary concern because that is what already sometimes happens.

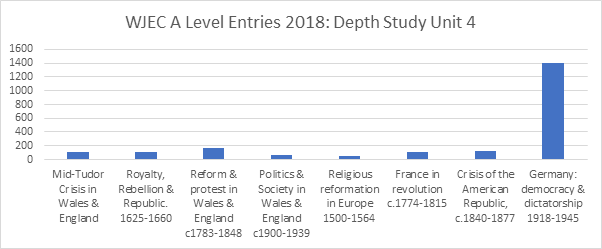

The existing national curriculum requires local and Welsh history to be ‘a focus of the study’ but, like its forthcoming replacement, it never defines very closely what that means in terms of actual practice. In some schools, it seems that the Welsh perspective is reduced to a tick box exercise where Welsh examples are occasionally employed but never made the heart of the history programme. I say ‘seems’ because there is no data on the proportion of existing pre-GCSE history teaching that is devoted to Welsh history. But all the anecdotal evidence points to Wales often not being at the heart of what history is taught, at least in secondary schools. At key stage 3 (ages 11 to 14) in particular, the Welsh element can feel rather nominal as many children learn about the Battle of Hastings, Henry VIII and the Nazis. GCSEs were reformed in 2017 to ensure Welsh history is not marginalised but at A Level the options schools choose reveal a stark preference in some units away from not just Wales but Britain too.

Why schools chose not to teach more Welsh history is a complex issue. Within a curriculum that is very flexible, teachers deliver what they are confident in, what they have resources for, what interests them and what they think pupils will be interested in. Not all history teachers have been taught Welsh history at school or university and they thus perhaps prefer to lean towards those topics they are familiar with. Resources are probably an issue too. While there are plenty of Welsh history resources out there, they can be scattered around and locating them is not always easy. Some of the best date back to the 1980 and 90s and are not online. There is also amongst both pupils and teachers the not-unreasonable idea that Welsh history is simply not as interesting as themes such as Nazi Germany. This matters because, after key stage 3, different subjects are competing for pupils and thus resources.

The new curriculum does nothing to address any of these issues and it is probable that it will not do much to enhance the volume of Welsh history taught beyond the local level. It replicates the existing curriculum’s flexibility with some loose requirement for a Welsh focus. Within that flexibility, teachers will continue to be guided by their existing knowledge, what resources they already have, what topics and techniques they already know work, and how much time and confidence they have to make changes. Some schools will update what they do but in many there is a very real possibility that not much will change at all, as teachers simply mould the tried and tested existing curricular into the new model. No change is always the easiest policy outcome to follow. Those schools that already teach a lot of Welsh history will continue to do so. Many of those that do not will also probably carry on in that vein.

Of course, a system designed to allow different curricula is also designed to produce different outcomes. The whole point of the reform is for schools to be different to one another but there may be unintended consequences to this. Particularly in areas where schools are essentially in competition with each other for pupils, some might choose to develop a strong sense of Welshness across all subject areas because they feel it will appeal to local parents and local authority funders. Others might go the opposite way for the same reasons, especially in border areas where attracting staff from England is important. Welsh-medium schools are probably more likely to be in the former group and English-medium schools in the latter.

Moreover, the concerns around variability do not just extend to issues of Welsh identity and history. By telling schools they can teach what they feel matters, the Welsh Government is telling them they do not have to teach, say, the histories of racism or the Holocaust. It is unlikely that any school history department would choose not to teach what Hitler inflicted upon the world but they will be perfectly at liberty to do so; indeed, by enshrining their right to do this, the Welsh Government is saying it would be happy for any school to follow such a line. Quite how that fits with the government’s endorsement of Holocaust Memorial Day and Mark Drakeford’s reminder of the importance of remembering such genocides is unclear.

There are other policy disconnects. The right to vote in Senedd elections has been granted to sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds. Yet the government has decided against requiring them to be taught anything specific about that institution, its history and how Welsh democracy works. Instead, faith is placed in a vague requirement for pupils to be made into informed and ethical citizens. By age 16, the ‘guidance’ says learners should be able to ‘compare and evaluate local, national and global governance systems, including the systems of government and democracy in Wales, considering their impact on societies in the past and present, and the rights and responsibilities of citizens in Wales.’ Making Wales an ‘including’ rather than the main focus of this ‘progression step’ seems to me to downplay its importance. Moreover, what this sentence actually means in terms of class time and knowledge is up to schools and teachers. Some pupils will be taught lots about devolved politics, others little. The government is giving young people the responsibility of voting but avoiding its own responsibility to ensure they are taught in any depth what that means in a Welsh context.

The new curriculum will thus not educate everyone in the same elements of political citizenship or history because it is explicitly designed to not do so. Just as they do now, pupils will continue to leave schools with very different understandings of what Wales is, what the Senedd does and how both fit into British, European and global contexts. Perhaps that does not matter if we want pupils to make up their own minds about how they should be governed. But, at the very least, if we are going to give young people the vote, surely it is not too much to want them to be told where it came from, what it means, and what it can do.

But this is not the biggest missed opportunity of the curriculum. Wales already has an educational system that produces very different outcomes for those who go through it. In 2019, 28.4% of pupils eligible for free school meals achieved five A*-C grade GCSEs, compared with 60.5% of those not eligible. In 2018, 75.3% of pupils in Ceredigion hit this level, whereas in Blaenau Gwent only 56.7% did. These are staggering differences that have nothing to do with the curriculum and everything to do with how poverty impacts on pupils’ lives. There is nothing in the new curriculum that looks to eradicate such differences.

Teachers in areas with the highest levels of deprivation face a daily struggle to deal with its consequences. This will also impact on what the new curriculum can achieve in their schools. It will be easier to develop innovative programmes that take advantage of what the new curriculum can enable in schools where teachers are not dealing with the extra demands of pupils who have missed breakfast or who have difficult home lives. Fieldtrips are easiest in schools where parents can afford them. Home learning is most effective in homes with books, computers and internet access. The very real danger of the new curriculum is not what it will or will not do for Welsh citizenship and history but that it will exacerbate the already significant difference between schools in affluent areas and schools that are not. Wales needs less difference between its schools, not more.

Martin Johnes is Professor of History at Swansea University.

This essay was first published in the Welsh Agenda (2020).

For more analysis of history and the Curriculum for Wales see this essay.

Education, the decline of Welsh and why communities matter more than classrooms

This article was first published at https://nation.cymru/opinion/education-the-decline-of-welsh-and-why-communities-matter-more-than-classrooms/

Why Welsh declined is an emotive topic. For more than a hundred years, some have liked to blame the British state, with the Welsh Not offering an apparently convenient symbol of official attitudes. Others prefer to argue that wider state attitudes deliberately created an atmosphere that encouraged people to turn against their own language. Either explanation frees Wales from responsibility for the decline of Welsh (although the former misunderstands how education actually worked and the latter implies that the Welsh of the past were gullible victims of some wider conspiracy).

What is beyond debate is that the history of the Welsh language in the modern period is one of decline. Probably at least 80 percent of the population spoke Welsh at the start of the nineteenth century and most of them could not speak English. At the 1891 census, the first time anyone counted properly, Welsh was only spoken by half the population, with 30% saying they were unable to speak English (although that figure was thought to be exaggerated because of the way the question was worded and some suspicion whether it could really be that high). By the 2011 census, just 19 percent of the population spoke Welsh and that figure was probably an exaggeration of actual fluency levels. Only in Gwynedd and Anglesey were more than half of people able to speak Welsh.

Education is part of this story but it is only part. If education was decisive to people stopping speaking Welsh, it is hard to explain why there were such large regional variations in language patterns. The central purpose of education in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was to teach people English but in rural Wales it often failed. In 1891 in Meirionnydd and Cardiganshire, three quarters of people were returned as only speaking Welsh, despite fifty years of growth in the education system. In 1901, 10% of 15-year-olds in Wales were unable to speak English, despite the fact that school attendance had been compulsory for more than 20 years. In rural districts of Meirionnydd more than half of 10 to 15-years-olds were unable to speak English.

Today, the education system is sometimes condemned for teaching English to the Victorian Welsh. But in that period, people damned it for failing to do so. The reasons given by investigations into education were

- Too many schools failed to make use of Welsh in the classroom and thus left children floundering to understand lessons given in what was essentially a foreign language.

- School lessons were not being reinforced by wider culture in communities where Welsh was the language of work, play and prayer and English was very rarely used or even heard.

Thus education did not bring about significant linguistic change in rural communities because it often failed to actually teach people to speak English properly. At schools where teachers refused to use Welsh, children might learn to read and repeat English words but they did not actually know what these words meant because no one ever told them and because they never heard them outside class.

Moreover, even if education had been better there was little to be gained in Victorian rural communities through abandoning Welsh. The language was spoken everywhere and by nearly everyone. Giving it up would have made no sense. It was both natural and useful, whatever the Blue Books said.

In contrast, in the industrial south communities were becoming more diverse. By the end of the 19th century, large-scale migration from England was affecting a shift in community languages. English became something that could be learned not just in the classroom but in the workplace, the pub and the street. Surrounded by an increasing number of workmates and neighbours who could not speak Welsh, the dynamics of language were changing from migrants learning Welsh to the existing population learning English.

Contemporaries noted how the key linguistic shift was among the children. They might speak Welsh at home but, in communities full of migrant children unable to speak Welsh, they played and learned in English and thus English came to be their natural tongue for speaking to anyone who was not their parents. They, in turn, raised their own children in English.

Thus demographics were key to why Welsh remained strong in the countryside but was declining in industrial and urban areas. There were, of course, other factors at play. The public rhetoric that Welsh was old fashioned and unsuited to modern life must have had some influence, although this has to be set alongside the very significant status Welsh gained by being a language of religion. English was also the language of a global mass media and popular culture. It was the language of a growing consumer culture and the army. This meant after the First World War, English made significant inroads into rural communities and in industrial communities the linguistic shifts brought about by demographic changes were reinforced.

It was only once English was well established that some Welsh-speaking parents took the decision to raise their children in English. Here they were influenced by the economic, political and cultural power of English but this trend was concentrated in the areas where English already dominated. Thus in 1926/7, of those children at Anglesey secondary schools who did not speak Welsh at home, only 2% had two Welsh-speaking parents. In Merthyr, 30% of secondary-school pupils who spoke English at home had two Welsh-speaking parents. In wider Glamorgan, the figure was 19%.

It is still instructive that a few families in Welsh-speaking Anglesey were raising their children in English. Yet the 1920s was relatively late and by then better education, military service, the cinema and radio had all boosted people’s ability to speak English. Before the First World War, it was more common for migrants into rural communities to learn Welsh than it was for locals to drop the language. Census records show how the children of English families who had moved to rural Wales could often speak Welsh. Their parents didn’t speak the language and much of their schooling would have been in English. It was in the community and with their friends that they learned Welsh.

Even in the first couple of decades of the post-1945 period, as the inability to speak English started to disappear, rural Wales remained strongly Welsh speaking, despite the allure of English films, tv and pop songs.

What changed this was not education or the status of languages but English migration. Just as migration from England was decisive to the decline of Welsh in industrial communities, it became decisive in the decline of Welsh in rural communities. Children of migrants might still learn Welsh but they do so most effectively in places where Welsh remains the dominant community language. The number of such places is falling as the demography of rural Wales changes.

What happens in schools only really matters if it is reinforced by what happens outside school. That is why today, decades of Welsh-medium education in English-speaking communities have not changed the language of those communities. It is why some children who learn Welsh lose it in later life. It is why Welsh-medium education for all in rural communities is not enough to buttress Welsh there if the everyday language of those communities is changing through migration from England.

If the Welsh Government wants to reach a million speakers then education alone is not the answer. Even if this nominal target is reached through a massive expansion of Welsh-medium education, it will not mean there are a million who do speak Welsh, merely a million who can speak Welsh. The decline of Welsh was rooted not in what happened in classrooms but what happened in communities. The future of Welsh won’t be saved by education either. It relies on ensuring there are still communities where it is natural to start a conversation with a stranger in Welsh. It relies on people elsewhere having other opportunities to use the Welsh they learned at school. It relies on being a living language outside the classroom.

Indeed, it’s probably better, and certainly more sustainable, to have 500,000 people regularly speaking Welsh in their community than a million able to speak it but rarely doing so.

Emotions, the Welsh Not and getting to know a Victorian headmaster.

As part of a project looking at the suppression of the Welsh language in 19th century schools, I have spent some time this week reading the logbooks of elementary schools. These were diary-like records of school life that headmasters were required by law to keep from the 1860s.

Given there were hundreds of schools in Wales, knowing where to start is a daunting task. Ideally, I would like to read every one and come up with stats that quantified the different approaches to the Welsh language. That would be a huge task and one where the outcome would not be worth the effort since most don’t actually seem to make many references to Welsh at all.

Thus I’m being selective in which ones I look at. This morning I concentrated on a school in the Gwaun valley in Pembrokeshire. This was because I had come across a 1920s letter to a newspaper from a man who recalled the Welsh Not being used there when he was a pupil in the 1880s.

Given the school’s single teacher, one Mr Llewellyn, was a man who apparently punished his pupils for speaking Welsh, I began reading with a disapproval of him. Maybe the historian should not start with a sense of judgement about the people being studied but I think that’s impossible. We certainly have to be careful of judging the past through modern values but this just means remembering the judgments being made and thinking about how that affects interpretations.

In this case, I did not feel too bad about expecting to dislike Mr Llewellyn because the Welsh Not was unusual by the 1880s. Most of education seems to have moved on by then and Mr Llewellyn was behind the times.

Unfortunately, the log book made no reference to the Welsh Not at all or indeed give any clue that his pupils did not speak English when they started school. Instead, the section from the 1880s was one sustained weather record and a repeated moan about very poor attendance and the impact of this on school learning.

At first, this was not very informative but gradually a picture of rural school life emerges. And the more I read, the more I began to feel sorry for the poor teacher. He despairs about how he can teach when half the school are regularly absent. Rain, snow and heat all keep children at home because many had to walk some miles to get there. So, too, does hay making, crop sowing and harvesting, local fairs and chapel meetings. Some children go three or four months without turning up. Many simply say when they do eventually attend that they were needed at home.

The inspection reports the school received were scathing and a copy of each one was handwritten into the logbook by Llewellyn. This in itself cannot have been a pleasant task. They question his physical ability to run a school alone. At first, I thought this meant more staff were needed but the second reference to this implies that he is not fit or healthy enough. I picture an ill man. The reports also question why some pupils are not there on inspection day, implying that they are being kept away so as not to affect the exam results. Arithmetic and sewing are the only subjects that seem ok, perhaps because they did not require English-language skills.

The School Board comes in for criticism too. More needs to be done about absenteeism and Llewellyn needs an assistant. There are no inkwells. The poor reports lead to cuts in the school’s government grant. I magine a frosty relationship between Llewellyn and the board that empoys him. Llewellyn records at one point: “The teacher is altogether blamed when an unfavourable report is given at the annual inspection of the school”.

Eventually one Summer holiday he resigns. Perhaps he had no choice. But after ploughing my way through 150 pages or so of his handwritten laments, I feel rather sorry for him and have forgotten how he used the Welsh Not. Maybe the picture in my head of a bent, elderly and frustrated teacher working to the ends of his wits is wrong. Maybe he took out his frustrations on the children and was vicious and bad tempered with them. The possibility of my sense of him being wrong is why the sympathy I developed should not shape the analysis. But it did shape my emotional experience of doing the research.

Whatever the poor standard of education in the school or the evils of the Welsh Not, forty years later one of his pupils exhibits no anger in recounting that this small peice of wood was ‘considered one of the most serious sections of the day’s curriculum’. Indeed, he relates the story of a farm boy turning up late to school and explaining to the others “Our donkey had a small donkey”. He was asked when but confused this for the Welsh word for white (wen) and replies “Nage, un ddu” (No, a black one). For this, he was presented with the Welsh Not. The letter does not record what the punishment was.

Such humorous stories of confusion were not uncommon in recollections of the Welsh Not. Like the experience of archival research, they are a reminder that emotions are not always what we might expect. People, after all, are complicated and little in the past is straightforward. Decent people can still do bad things. People who have bad things done to them can still laugh. And the historian can feel for them both, without losing the objectivity needed for analysis.

The stories that bind us: history and the new curriculum

This weekend I attended an excellent event put on by the Cardiff Story museum about the 1919 race riots. The speakers included artists and activists from the Butetown community that was the victim of the 1919 racist attacks. There was a clear desire among both speakers and the audience that the riots be remembered and that the community be allowed to tell its own history.

Theatre events, poetry and art are allowing the riots to be remembered now, but ensuring the memory lives on beyond its centenary is less straightforward. There was a clear ambition voiced at the event to see the riots, and black history more generally, placed on the Welsh national curriculum.

The national curriculum in Wales is currently undergoing a radical redesign but it will be based around specific skills rather than specific knowledge. Thus in history there will be no requirement that any particular event or person is taught. Similarly, in English and Welsh literature, there will be no poet or novelist who is required reading.

Teachers and schools already have some choice about what they teach but now they will be given free rein to use whatever content they like to meet the curriculum’s overall requirements of ensuring pupils are

- informed citizens of Wales and the world

- ambitious and capable learners

- enterprising and creative contributors to society

- healthy and confident individuals.

The curriculum also requires that the Welsh context in which pupils live should be central to all these ambitions.

Teaching pupils about the race riots of 1919 would certainly fit with the curriculum’s ambitions and there would be nothing to stop schools using it as a way of both teaching about the past and encouraging thinking about the dynamics of race today. However, the new curriculum will not allow this to be a requirement. If it happens, it will have to be the choice of individual teachers and schools.

As someone in the audience at the 1919 event stated, this means that there is no guarantee that children will learn about the riots and the racism they involved. It may be, it was suggested, that some white teachers will not see ensuring such things are taught as important.

The same fears exist among those who want every child to learn about other specific events that are central to the history of Wales. There is no guarantee that any pupil will learn about medieval conquest, the flooding of Tryweryn, the Second World War, the struggles for civil rights, or the rise of democracy. Some children will learn about all these things but future citizens’ knowledge of history could vary significantly according to which school they attend.

This has implications for the very nature of Welsh society. The curriculum is intended to foster a sense of Welsh citizenship and to put that in a global context. The question is whether that can be achieved when every child is learning about Wales through different sets of knowledge.

Wales is a diverse place and Welshness means many different things. A curriculum that reflects this, and a nation that is comfortable with a plurality of knowledge, is a mature one. A curriculum that demands every child learn the same ‘national story’ is perhaps something that only a country unsure of itself would produce. Such a story would also inevitably lead to considerable controversy about what it should include. And that is before any consideration of how events should be interpreted.

No historian would argue that there is a single simple Welsh story that could be taught. The past is both vast and complex. Deciding what matters is a political decision. So, too, is explaining why something matters. Giving power to schools and teachers does not overcome that but it does at least free the curriculum from the kind of government interference Michael Gove tried to enact in England in 2013 with his plans for a revised patriotic history curriculum.

Yet teachers are political too, and they do not operate in value-free environments. Their own interests and experiences will influence what they decide to teach. They will, inevitably, reproduce some of the existing outlooks instilled in them by their own education.

Thus those who hope the new curriculum will lead to a flourishing of Welsh history may find it doesn’t because of the existing lack of Welsh history taught in schools and universities. Those who hope it will lead to more teaching about the diversity of Wales may find it does not because that diversity is so often invisible in existing practices. Where teachers come from, where they go to university and who they are will have profound influences on the evolution of the new curriculum.

The freedom the curriculum gives teachers is both its strength and its weakness. It should allow teachers to tell the stories of their own communities and to give them and their pupils a sense of ownership over those histories. It is certainly a recognition of teachers’ professional standing and experience. It should give them the opportunity to innovate and develop exciting programmes that inspire our children.

But it will also be up against the challenges of time and resource that teachers face. It will be up against the real socio-economic inequalities which exist and which challenge teachers in their daily working lives. It will be easier to develop innovative curricula in schools where teachers are not dealing with the extra demands of kids who have missed breakfast or who have difficult home lives. The very real danger of the new curriculum is that it will exacerbate the already significant difference between schools in affluent areas and schools that are not.

The age of devolution has seen too many excellent policies flounder because of how they were (or were not) implemented. There will be an onus on government to ensure that schools are not cast adrift and left to work out things for themselves. They need support and, I suspect, a whole host of exemplar programmes to show the curriculum can work in practice. If those exemplars are of high enough quality, schools will adopt them. It is through such exemplars and resources that there is the best opportunity to ensure the important themes and events in our history are taught in our schools.

In Game of Thrones, Tyrion Lannister claims that it is stories that bind people together. He is right. History’s stories can inspire, empower, liberate and unite us. It is not necessary that everyone knows all the stories. It will be impossible to agree which stories matter most and how they should be taught. There is nothing wrong with empowering the storytellers to make those decisions. This makes political and pedagogical sense.

But I also cannot help worrying that the new curriculum might further fragment society. Despite my belief that all histories are equally valid, I cannot escape a nagging doubt that it would be wrong if children did not what know the basics of what happened in the Second World War or that people of colour have a long and rich history in Wales. 1919 is a reminder of what can happen when societies are not bound together. It should not be forgotten.

Goodbye, Mr Chips, modern education and the REF

Last night I watched a lovely 1939 film called Goodbye, Mr Chips. In it, an elderly teacher rallies against the Headmaster of the public school he has spent his career at:

I’ve seen the old traditions dying one by one. Grace, dignity, feeling for the past. All that matters here today is a fat banking account. You’re trying to run the school like a factory for turning out moneymaking machine-made snobs! You’ve raised the fees, and in the end the boys who really belong to Brookfield will be frozen out, frozen out. Modern methods, intensive training, poppycock! Give a boy a sense of humor and a sense of proportion and he’ll stand up to anything.

Historians more than anyone should be aware of the dangers of nostalgia but as universities spend the next few days pondering, proclaiming and panicking over the results of the Research Excellence Framework, it will be difficult not to think this is not what education should be about.

The Victorian public school system is hardly a model for what universities should be doing in the 21st century but Mr Chips understood that education is about far more than things that can be quantified, monetized and put into boxes or league tables.