Martin Johnes and Iain McLean

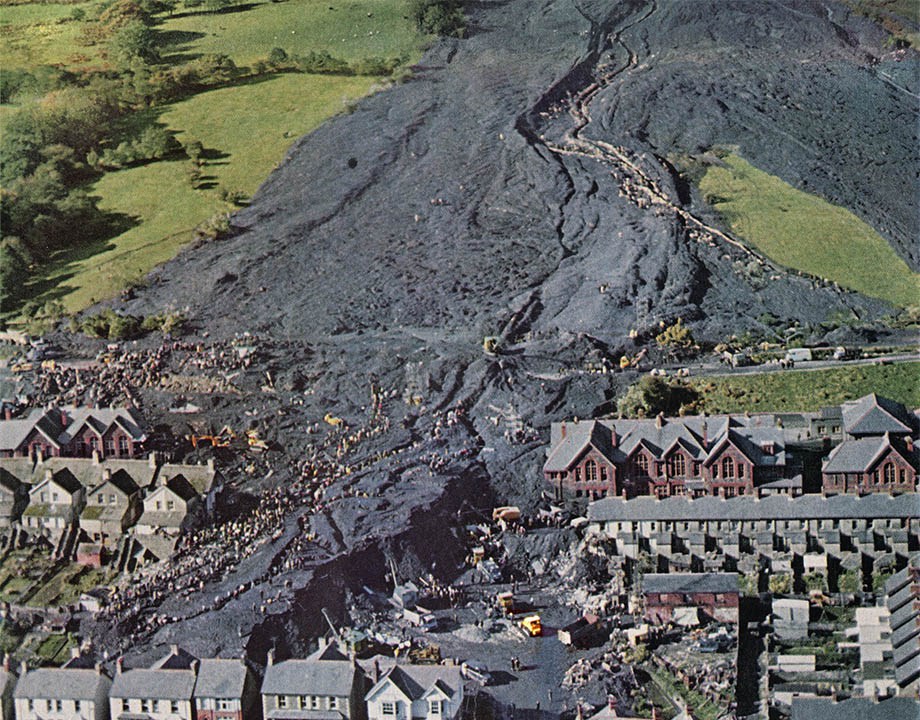

On Friday, 21 October 1966 a coal tip slid down a mountainside into the mining village of Aberfan in the South Wales valleys. The slide engulfed a farm, around twenty houses and part of the local junior school before coming to rest. The disaster claimed the lives of 144 people, 116 of whom were school children. The horror felt around the world was made all the more poignant as news emerged of previous slides and brushed aside warnings. Such was the widespread sympathy that was felt that a fund set up to help the village raised £1,750,000.

A terrifying tale of bungling ineptitude

In the days after the disaster, Lord Robens, chairman of the National Coal Board (NCB), attributed the tragedy to ‘natural unknown springs’ beneath the tip. This was known by all the local people to be incorrect. The NCB had been tipping on top of springs that are shown on maps of the neighbourhood and in which village schoolboys had played. The government immediately appointed a Tribunal of Inquiry. Its report was unsparing:

Blame for the disaster rests upon the National Coal Board … The legal liability of the National Coal Board to pay compensation for the personal injuries (fatal or otherwise) and damage to property is incontestable and uncontested.

These dry conclusions belie the passion of the preceding text. The Tribunal was appalled by the behaviour of the NCB and some of its employees, both before and after the disaster:

the Aberfan disaster is a terrifying tale of bungling ineptitude by many men charged with tasks for which they were totally unfitted, of failure to heed clear warnings, and of total lack of direction from above

Colliery engineers at all levels concentrated only on conditions underground. In one of its most memorable phrases, the Report described them as ‘like moles being asked about the habits of birds’.

The Tribunal endorsed the comment of Desmond Ackner QC, counsel for the Aberfan Parents’ and Residents’ Association, that coal board witnesses had tried to give the impression that ‘the Board had no more blameworthy connection with this disaster than, say, the Gas Board’. It devoted a section of its report to ‘the attitude’ of the NCB and of Robens and forthrightly condemned both.

Corporate responsibility

In the face of the report, it now seems surprising that nobody was prosecuted, dismissed, or demoted or even said sorry.

It is also surprising that Robens’ offer to resign as NCB chairman, which even at the time was seen as perfunctory, was rejected. Public records released under the thirty year rule, show that he had advance sight of the tribunal report and his private office ran a media campaign to keep himself in place. Through very public attacks on government fuel policy, he was able to portray himself as a defender of the industry and win the support of the unions. This was not a new line for him to take but Robens was a great PR manipulator and he knew that he was securing his position. Ministers let him stay, despite disliking him, because they thought he was the only man who could manage the decline of the coal industry and avoid strike action. In effect, Robens’ behaviour after Aberfan became irrelevant to whether he kept his job or not. Rather, political expediency was the name of the game.

Nobody suggested that Robens himself was to blame for the disaster but he was the head of the organisation that clearly was. The extent of mismanagement revealed by the Tribunal was such that the question of prosecution arose in Aberfan and the media. However the NCB itself avoided prosecution because the concept of corporate manslaughter was very much on the fringes of legal procedures. Mining was a dangerous industry where accidents were normalised as an almost inevitable part of operations. This is not to say that they were taken lightly but rather that they were seen as just that, accidents.

Accidents might be the product of individuals’ errors maybe but the idea that those errors could be fostered by a wider corporate culture that amounted to criminal negligence was simply not part of the contemporary agenda. When the question of manslaughter charges was raised it was with regard to individual employees not the NCB itself. Concepts of corporate responsibility, in and outside the coal industry, were essentially under developed. Thus, despite the evidence to the contrary, the Aberfan disaster did nothing to challenge the picture of disasters as tragic accidents rather than criminal negligence.

A catalogue of self-serving episodes

Other events that now seem surprising followed Aberfan. In August 1968, the government forced the trustees of the disaster fund to contribute £150,000 to the cost of removing the remaining NCB tips from above the village. These tips were in a place and condition in which, according to the NCB’s own technical literature, they should never have been. Yet the board refused to pay and even undermined the efforts of a rival firm offering to remove the tips for less money that the NCB thought it would cost.

The contribution was bitterly controversial. Some people wrote to ministers to complain that it was inconsistent with the charitable objectives of the fund; ministers’ replies did not address the point. The Charity Commission failed to intervene or even query the debatable point on whether such a contribution was legal. In contrast, it asked the disaster fund to ensure that parents were ‘close’ to their children before making any payment to them for mental suffering.

The villagers of Aberfan were traumatised beyond the comprehension of outsiders who could see only their ‘unpredictable emotions and reactions’. The trustees of Bethania chapel, which was used as the mortuary after the disaster, pleaded with George Thomas, the Secretary of State for Wales, to get the NCB to pay for it to be demolished and rebuilt, on the grounds that its members could not longer bear to worship there. Thomas passed the plea on to Lord Robens, who rejected it. Eventually it was rebuilt but at the expense of the disaster fund not the NCB.

The NCB paid just £500-a-head compensation to the bereaved parents. To some parents this was insultingly low. Coal board lawyers, however, regarded it as ‘a generous settlement’ and it was not at odds with other contemporary payments of loss of life by a child. Even as insurers wrangled, the ruins of the school and empty houses remained for a year.

For those in Aberfan, the legacy of this catalogue of self-serving episodes was a deep feeling of being let down and injustice. The result is a lingering mistrust of authority. It has also made the closure process difficult and undoubtedly hindered the healing process in the local community. Subsequent events served to exacerbate that feeling. In October 1998 the village suffered severe flooding. An independent inquiry showed that the flooding was exacerbated by dumped spoil from the removed tips. One survivor of the disaster and victims of the flooding said ‘I was buried alive in that tip in the disaster. Now it’s the same tip again dumped outside my door. It’s no wonder I am angry.’

A community on the periphery

George Thomas, Secretary of State for Wales and originally a teacher from the Rhondda, did initially protest at the decision to encourage the disaster fund to contribute to the payment of the removal of the tips. But his lone voice in the cabinet was not sufficient and in the end he acquiesced in the plan and placed strong moral pressure on the disaster fund to ensure it too gave in.

There was considerable local anger but the South Wales valleys consisted of safe Labour seats. All the major Labour figures knew that the rising Plaid Cymru support in the valleys was essentially just a protest that would pass. The Labour hegemony thus condemned Aberfan to the margins. In contrast, Robens’ ability to avert a coal strike was very much the concern of government and he kept his job as chairman of the NCB.

Gwynfor Evans, leader of Plaid Cymru, complained in the parliamentary debate on the disaster that if the tips had been at Hampstead or Eton, the Government would have taken more notice. Aberfan was a small working-class community isolated from the heart of UK politics. The government’s decision to grant legal aid to the Aberfan Parents and Residents’ Association at the Tribunal of Inquiry did mean they were able to afford the best ‘silk’ of the day. The fearsome Desmond Ackner triumphed over the NCB at the Tribunal. But in the aftermath of the disaster, a Labour government, whose support across South Wales was secure, ignored Aberfan’s interests.

The disaster itself, of course, was not marginalised. The London media, Royalty, and the Prime Minister all travelled to Aberfan to see the horror for themselves. It was only a few hours drive away or an even shorter flight. Even Lord Robens got there, 36 hours later. Politicians were undoubtedly personally touched by the disaster. Harold Wilson noted that when he visited a Cornish school less than eight days after the disaster, he felt ‘almost a sense of resentment at these happy innocent children, with all they had to look forward to, compared with the children of that Welsh valley, who had no future.’ Intensive media coverage, particularly television, ensured that the disaster was seen as a national one.

Yet this was not enough to overcome the residents of Aberfan’s position on the political periphery, something that had contributed to the causes of the disaster and intensified the injustices after it. The disaster simply would not have happened had the NCB taken local fears about the tips more seriously or enforced its own rules on tip safety. But it was an organization hampered by mismanagement yet protected from market and political pressure by being part of the state and a dominant local employer.

Before the disaster, the NCB’s economic and local political power meant no one, including the small local authority in Merthyr, was able to challenge it to do more about fears on tip safety. After the disaster, the NCB’s economic and national power meant its interests took precedent over those whose children it had killed.

Martin Johnes and Iain McLean are the authors of Aberfan: Government and Disasters (Welsh Academic Press, Cardiff, 2019).